A young man struggles to process his grandfather’s death

September 15, 2022 | Story, photos and illustration by Bryce Brown

“Who is that?”

No one else was in the room.

“Who, Papa?”

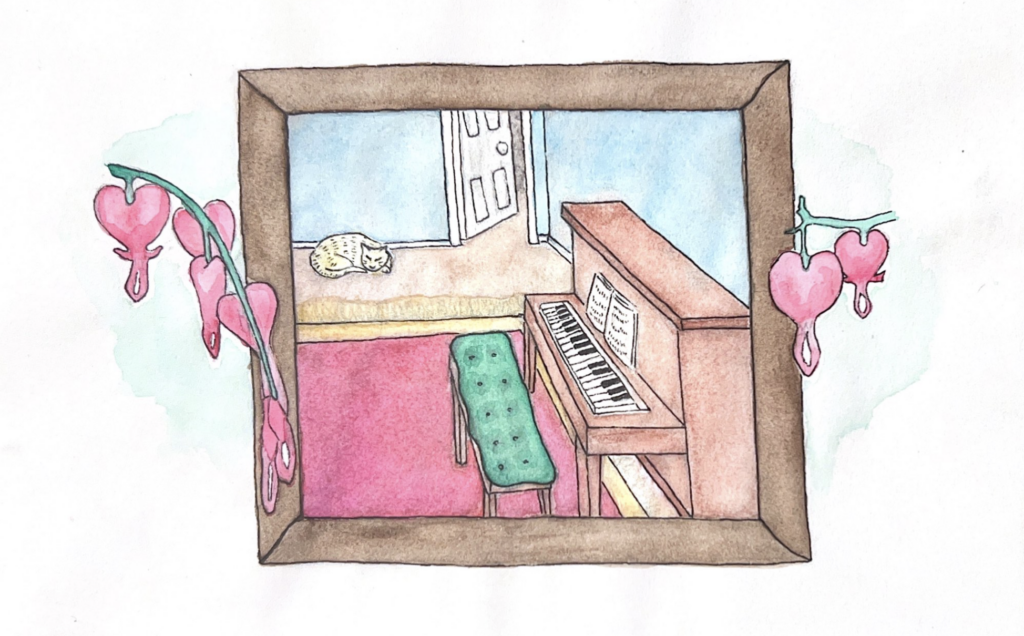

“The boy standing there,” he said. He pointed to the corner of the piano room. The hospice nurses placed him there because it was the only space that could accommodate his hospital bed.

When he began to hallucinate, I knew I could no longer talk to him and expect him to understand me. He was floating in a pool of morphine; he seemed very peaceful.

I wanted to know who the boy was, and I often told myself it was him as a child. I liked the idea of him revisiting his past in his dreams, different memories from his life flitting behind his eyelids.

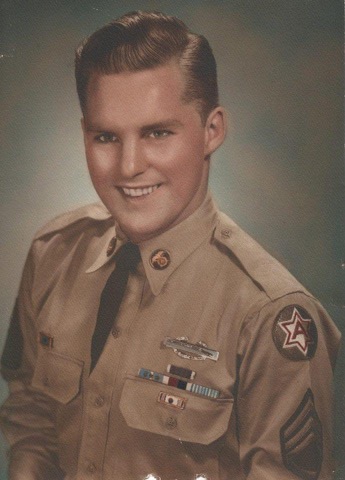

Perhaps he was in Missoula at that moment, back in the pulp mill where he worked for 33 years and took only three sick days off. Or maybe he was in Korea, in that little shed with his comrade where they both sat with holes in their legs, begging the sun to rise.

Papa always told me that story. About how he and his friend sat wounded in the dark when two enemy soldiers found them and pummeled on the door of their wooden hiding place. The door was unlocked, but the two men couldn’t get in. Papa said God sent a guardian angel to protect them that day.

Papa smiles as a young military sergeant in the Korean War. He weathered brutal suffering and yet, his faith persevered.

There were several visits over the course of the following few days: from the boy, from a chicken and from a yellow cat.

“Where did that cat come from? You see it?”

“Sure, I see it. The kids brought it home, Papa,” Mom said.

He desperately wanted us to catch the two loose animals in his room. We tried our best.

“Have you made any plans for the funeral?” asked the nurse.

Mom’s nostrils flared.

“N-no, we didn’t,” she said. “And I don’t think we need to discuss that right now.”

Her eyes flittered to Papa, who lay in bed beside them. He raised his right hand, placed it behind his head, closed his eyes and smiled.

Papa rarely got angry. He didn’t have the harsh evangelical hand like Grammy. He was patient. He would listen to me read to him. He enjoyed Disney movies and chocolate milkshakes from Dairy Queen. He could imitate Donald Duck quite well, and we used to say he looked just like Mr. Fredricksen from “Up.” He loved trips to Costco. He was famous for his salmon; his recipe made it into an RV magazine. He used to say Grammy was madder than a wet hen. He used to call her cutie pie.

Papa and Grammy at Coeur d’Alene, Idaho, in 1995. His gentle temperament balanced her fire.

Papa was having trouble swallowing. That was how he first noticed something was wrong. My sister and I fed him chocolate ice cream most afternoons because that was one of the few foods he could get down, and it happened to be his favorite.

When I spooned the cold, creamy dessert into his mouth, he suddenly looked much younger. It felt as though we had switched roles. Child and adult. Dependent and caregiver. It seemed that the closer he approached death, the more childlike he appeared. To reunite with one’s beginning at their end was beautiful to me.

When I was growing up, he would sit at the window and watch my sister and me play sharks and minnows in the pool or tag in the grass. We liked to sneak downstairs where he and Grammy lived and pretend to be spies on a secret mission until one of them caught us. Although he wouldn’t admit it, he loved it when we did that.

Around this time, I developed a habit of sleeping on my parents’ bedroom floor. Nestled between the bed frame and the chaise lounge in my makeshift bed, I could hear the soft sounds of “Tom and Jerry” rising through the floor. We rarely turned off the TV in his room; I imagine because the cat and mouse kept him company when all others were away. The animated voices hummed below me, lulling me to sleep each night.

As the summer grew tired, so did Papa. Sleep wrapped its arms around him, placing an immeasurable weight on his frail frame so he sank further into the sterile sheets of the hospital bed that sat like a festering sore in the study. I couldn’t remember the last time he opened his eyes; the subtle rise and fall of his chest was the only movement in the room.

On his 83rd birthday, Papa sits in the backyard of his family’s Massachusetts home. On summer days there, he found comfort in his grandchildren’s childhood whimsy.

Outside his window, the bleeding hearts and lilies bloomed. The weather was sultry; the air thick and heavy. As a child, I thought this was heavenly. This meant pool days. This meant tuna fish sandwiches and ice cream. This meant pruned fingers and rosy faces and friends. I thought about how Papa could no longer watch my sister and me swim in the pool. It seemed wrong that summertime and tragedy could occur simultaneously, so some days I tried not to think about the man dying in the other room.

He passed away while I was eating my cereal.

I found it peculiar Papa died in that house, in that room in Massachusetts. It seemed far away from everything. The day was ordinary; it felt arbitrary. The July sun drenched the garden; the pool cleaner arrived; the birds ate from their feeders; Dad went to work.

Mom closed his eyes that morning before she told me. She asked me to go upstairs and tell my sister. As I climbed the stairs, the air around me felt lighter. I considered whether this was what relief felt like.

When I entered my sister’s room, my throat tightened, and I forgot what I wanted to say. My mind scrambled to find the words, and when my lips parted, I laughed. I couldn’t suppress the giggles that swam up my throat when I told her Papa died, and I could feel my face grow red. She stared at me. Then she told me not to joke about things like that.

We both kissed him on the forehead and gave him one final hug. When the coroner came, Dad returned from work and took us out to get lunch. He tried to be what he likely envisioned a good parent would be at a time like this.

“How are you feeling?”

“Fine.”

He was never very good with the emotional stuff. But neither were we.

Storm clouds sauntered across the afternoon sky at their usual time. I didn’t understand why my mood didn’t match the weather. I didn’t know why I hadn’t shed any tears, and I tried to avoid questioning it. It was a quiet, pleasant day. It felt as though the summer had been liberated; I hated myself for thinking that.

We brought Papa’s ashes to Montana in late August, where a small crowd gathered for his funeral service. Only one of his six children came. But so did a distant friend. And a former colleague. A neighbor. They spoke about how he could build anything out of nothing. How he would lend a neighbor sugar if they asked for it. They spoke about how God is so gracious for laying him down gently; how we’ll all join him one day. They said the sun still rises in the winter, and the beast of grief can take on many forms. They said he’s watching over us; they told me to read to him.

It was my turn to speak.

I began to cry.