A mother and daughter bond over Senegalese curry

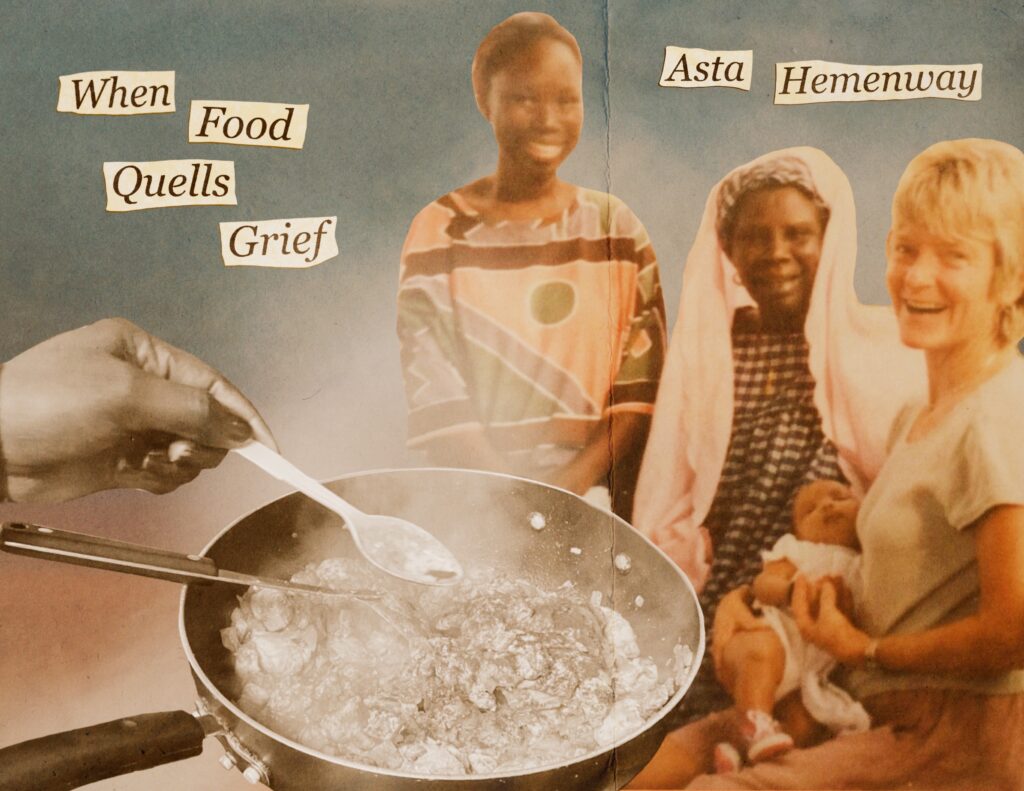

April 1, 2022 | Story by Asta Hemenway | Photo illustration by Dominica Davis

This memoir is part of Atrium’s Winter 2022 issue. To view the print edition online, visit our Issuu here.

It was still too early for dinner. The sun beamed down on my sweaty, carefree siblings, who negotiated another 10 minutes to squeal on a battered swing set in our backyard.

But there she was, lurching her slim frame over the pot of dancing hot oil and chicken.

My mother stood on her tiptoes to stir before turning to me. Trying to escape her glance, I pretended to do homework. But she doesn’t fall for my tricks, so she asks anyway.

“Asta, can you chop the onions for me?”

“Maybe you can finally learn how to make this curry,” she whispers under her breath.

“Heard that, mom.”

“So? You should,” she says, placing her hand on her hip.

As I’m snailing toward the kitchen, she sprinkles in the secret seasoning from a yellow box. She refuses to tell me what’s in it.

Ugh, I’m never gonna learn this recipe.

She tells me to watch the pot because she’s going to drag the negotiators — my siblings — inside before timis, a Wolof word for twilight or “demon-time.” Afterward, she’ll lie down and watch “90 Day Fiancé,” a show I believe she loves because it reminds her of how she married my father.

She’s entrusted me with the curry, and it’s nearing a yellow, soft-brown color. It’s almost ready.

The negotiators and I prefer when the curry is a deeper brown. It tastes sweeter and is goopier; the spice is less traumatizing to my tongue. But that flavor means it must burn more. My mother only serves curry like that if it’s by accident. It’s not how she learned to make it.

A few minutes later, she steps back into the kitchen and sees the darkened chicken. A sharp whistle of air flies through her teeth. She dishes us some anyway.

She snags a bite. She’s quiet. It’s good.

When my grandma passed away suddenly in January 2018, our routine stopped. The dish reminded my mother too much of the place she called home, too much of who she lost. It was a while before our taste buds would again water for the sweet spice.

I visited Maam N’Dawa for all of five times in Senegal, where the air is drier and dustier, the sun is unforgiving, but the people are warm. She watched my mother grow up. Then watched her move across the ocean.

Traditions helped tie them together despite distance. Their food, their memories.

My mother booked the earliest flight she could find in March that year, but the burial had already taken place before her visit. She couldn’t bear to cook curry, or any Senegalese food, for months.

We all felt powerless to help her pain. But like an ascending wave that breaks faster than it rises, my mother’s grief seemed to dissipate. She started to make curry again in the summer.

“Asta, can you chop the onions? It’s almost timis. I need to call those loud kids in.”

“Yeah,” I tell her. “maybe you can teach me this time?”