Taming the beast

Why riders get back on the bull

January 15, 2025 | story and photos by Alissa Gary

This story is from Atrium’s Winter 2024 magazine, which released December 2024.

Eight seconds.

That’s how long Bronc Platt needs to stay on K-00 Buckshot, the nearly 2,000-pound bull he’s straddling. Brown-furred and white-horned, the bull reels, its back arching into a U-shape and curling into a frown. Only two of its legs are ever on the ground at the same time. Spit flies in jagged patterns from its mouth.

The bull’s only objective? Get Platt off its back, now.

“Eight seconds is actually a lifetime,” Platt said.

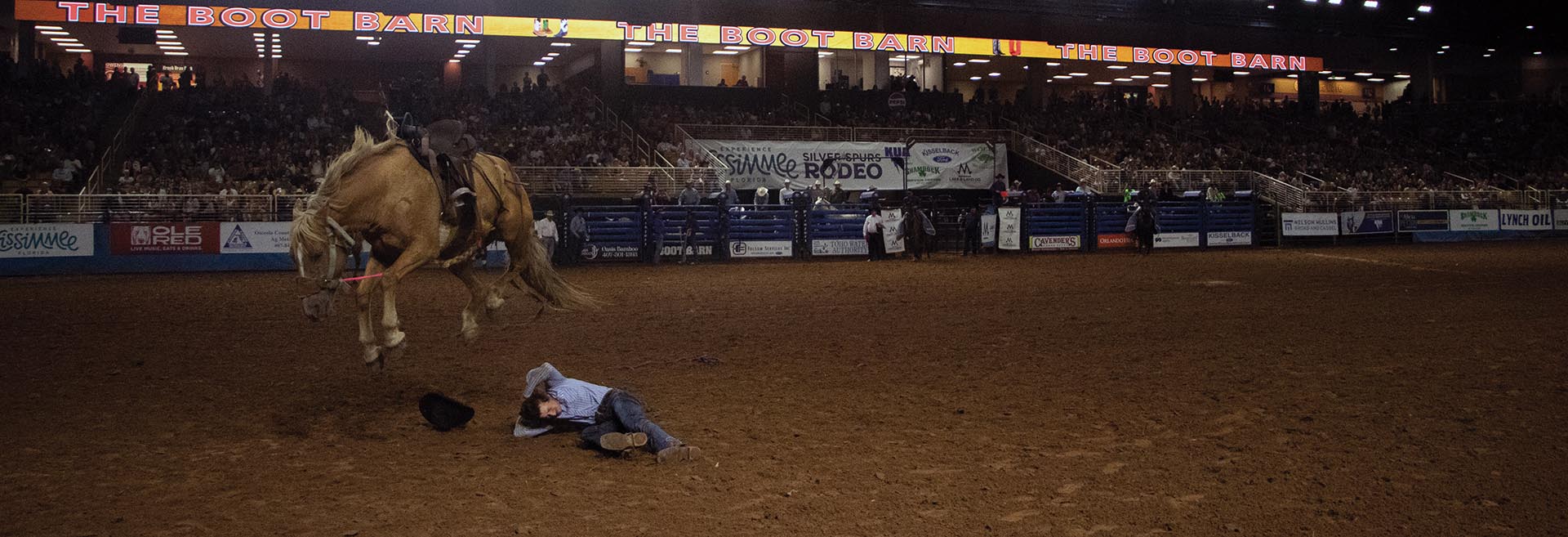

He grips the rope wrapped around the bull with just one arm, in accordance with the sport’s rules, and stretches the other arm toward the ceiling. When the bull bucks, Platt squeezes his center and moves with it, desperate to stay square on its back. But at 7.19 seconds, just short of the eight-second buzzer, K-00 Buckshot sent Platt pummeling arms-first toward the soft brown dirt on the rodeo floor.

At least this time, he didn’t break anything in the fall.

Platt, 34, knows the danger of bull riding. During a rodeo just five months earlier, a bull stepped on and crushed his lower stomach, breaking bones in his back and neck.

But this danger, as much as the excitement, is what makes bull riding popular. Though riders understand the risks of the sport, they keep getting back on the animals’ backs because, as Platt put it, riding is addicting. Athletes seek to conquer the bull — and, more importantly, to conquer the fear of losing to it.

“It’s better than any high, I reckon,” Platt said.

Like other rodeo sports, this one has influences from 19th century Mexican farm workers, who challenged each other to charreadas, offhand contests in lassoing or horseback riding. The sport was late finding an audience, only picking up steam through the mid-1900s.

Now, rodeo culture is inextricably tied to the rural American South and West, leaving an indent on the landscape in Kissimmee, Florida, too. The Silver Spurs Rodeo, where Platt rode K-00 Buckshot, calls itself the largest east of the Mississippi.

The sport has a simple objective: Stay on the bull for eight seconds, and you qualify for judging. A panel of judges then evaluates the ride, giving up to 50 points to the rider and 50 to the bull.

Hanging on for eight seconds is not easy. Even those who have ridden since childhood, Platt said, struggle to do it. If riders fall off the bull unsafely, they risk getting caught under the animal’s hooves and suffering major injuries.

When a bull trampled Platt in May, he was in recovery for nine weeks before returning to the arena. Now, he wears a white helmet with metal grates and a heavy leather vest while riding.

“He pinched me like a lawn chair,” Platt said. “He folded me in half, and I knew I was hurt, but I toughed it out pretty good.”

Other rodeo events, including one where athletes attempt to ride a bucking horse, also have high injury rates. But bull riding is the most perilous of them all, according to researchers at the University of Oklahoma. Bull riding caused the highest percentage of injuries from the 2,100 rodeo athletes who were studied.

There could be even more rodeo injuries than those recorded, the researchers wrote. Rodeo athletes tend to have high pain tolerance and opt to “shake off” their wounds rather than seek treatment for them.

Platt, too, prides himself on his toughness. “If you don’t mind it, it don’t matter,” he says about the pain. “Mind over matter.”

When Platt gets hurt, he avoids the hospital, allowing the injury to heal itself — or until the pain becomes unbearable. He’s wary of medical care. (A close call with opioid addiction following a bull riding accident means he rejects most painkillers today.) In 2017, he woke up in an ambulance with puffy eyes and a shattered nose, and he saw, through blurred vision, a bald, sweaty EMT standing over him.

“Oh my god,” Platt recalls the medic saying. “You’re alive!”

Bronc Platt, 34, Cheyenne Costello, 35, and their daughter Hazie, 4, stand outside their home in Citra, Fla. (Alissa Gary/Atrium Magazine)

At a rodeo in Inverness, a bull kicked him on the side of his head, knocking him unconscious and leaving his ears ringing for months. At the time, Platt blamed his helmet for weighing him down, pulling him toward the bull’s hooves. So, the day he returned to competition, he traded the helmet for a soft cowboy hat.

Professional Bull Riders, the sport’s leading league, has required helmets since 2013. But certain riders who are “grandfathered in” can skirt the rule, opting to wear hats instead. Platt has gone back and forth, settling eventually on a helmet after his 4-year-old daughter, Hazie Platt, begged him to wear one.

Hazie and her mom, Cheyenne Costello, cheer from the rodeo bleachers as Platt wraps his rope around the bull. Costello recently invested in a digital camera to take photos of the riders, but she said photos of Platt always turn out blurry. When it’s his turn to ride, her nerves keep her from holding the camera still.

“I get just as much of an adrenaline rush when he’s riding as he does,” Costello, 35, said. “My heart beats. I sweat. I shake. I get real nervous.”

A thin, brunette woman with hazel eyes and a sharp jawline, she knew when she started dating Platt five years ago that he rode bulls. She, too, grew up with rodeo in upstate New York — and even competed in barrel racing — so she understood rodeo was more a lifestyle than a hobby. In marrying Platt, Costello signed onto the anxiety that her husband might not make it home that night.

She’s the one who packs Platt’s bags and ensures his entrance fees are paid from their home in Citra, Florida. At competitions, she takes the role of team mom: Hungry riders swarm around her snack bag, and she volunteers to remove stitches and clean wounds when they can’t see a doctor. She’s seen other bull riders’ girlfriends come and go, she said, unable to keep up with the demands of the job.

“It’s really mentally straining,” Costello said. “Way more than anybody could really understand.”

Two hours before Platt came barreling out on K-00 Buckshot’s back, Jason Ragar and Dee Ragar took their front-row seats at the Silver Spurs Arena, where the rodeo took place. About 7,500 people this year attended the smaller of Silver Spurs’ events — a bull riding, barrel racing and saddle bronc showcase held in October.

The Ragars live in nearby Clermont, just west of Orlando. They’ve watched, with time, developers creep onto rural lands they called home. Kissimmee, home to the rodeo arena, is more known today for its proximity to Disney World than for its agriculture.

Like most cities in Florida, Kissimmee hosts a flat maze of suburban neighborhoods and paved roads. Hotels are packed densely into the city’s western corner, hoping to attract theme park tourists. But on the opposite end lie neighborhoods that are less crowded, where vast parcels of land are more common. There, nestled within a larger events fairground, stands the nearly 34,000-square-foot Silver Spurs Arena.

For the Ragars, the rodeo is a microcosm of how things used to be.

“It’s a lost entertainment,” Dee, 53, said. Country music poured from the arena speakers as she paused.

Silver Spurs, too, prides itself on its rural past. Its slogan reads “tradition rides on.” A promotional video, complete with black-and-white footage of vast 1940s agricultural lands, tells the inspirational story of a sport fighting to stay alive in a world that wanted it dead. “Life was simple back then,” the video says. “Oranges and cattle were king. It would be decades before a mouse named Mickey came to town.”

The rodeo reminds its fans that they’re not alone in their yearning for the past.

Jason, 55, is a rodeo regular whose favorite event is bull riding. He knows riders get injured all the time, but there’s something inherently exciting about watching other people put themselves in danger.

“It’s a throwback to more primitive times,” he said, “like almost gladiatorial.”

That night at the Silver Spurs Rodeo, the top prize went to Hagen Meeks, a 21-year-old bull rider from Polk City, Florida. The fringes on his teal-green chaps bounced as he rode, clashing with the bull’s milky-white fur. He was one of only two riders in the preliminary round who clung on long enough for judging, so he earned a spot in the finals.

When the eight-second buzzer finally sounded, it signaled time for his dismount. He needed to stay calm. “Look for a place to get off,” he said, “and just commit to that.”

He leaned his weight to the right, letting himself slide off the still-bucking animal and onto all fours in the dirt. As he scrambled to his feet, he pumped his fist in the air — he just secured another championship.

Meeks’ father took him to his first rodeo at 8 years old. It was then that Meeks decided he’d become a professional bull rider. Thirteen years later, he was finally riding in Professional Bull Riders competitions and, in September, won nearly $5,000 for placing second in Charlottesville, Virginia.

“Nothing else matters more than just getting the job done,” Meeks said. “The adrenaline and the blood rush — it’s like an addiction other than drugs.”

Amateur rodeos hand out a couple hundred dollars’ worth of prize money, but only the winners earn enough to cover their competition entrance fees. Professional Bull Riders, by comparison, represent the highest echelon of athletes in their sport, winning hundreds of thousands of dollars across their careers. Joining the Professional Bull Riders league means making a living, Meeks said.

Bronc Platt doesn’t ride in the professional league. Money has been tight. He and Costello once counted $13 worth of pennies to afford gas home from a rodeo in Georgia. His career, he said, is a gamble: With each ride, he could win or lose it all.

“They don’t pay the same,” he said of local competitions, “but they still buck the same.”

Costello cleans horse stalls and breeds dogs and chickens, the profits of which are their family’s sole consistent income. If Platt wins a rodeo, that’s added to their budget, too. Often, the money gets reinvested in competition registration fees.

Skipping a competition is not an option for Platt. He straddled his first bull at 3 years old, following in the footsteps of his father. His fate was sealed from the day he was born: How could a child named Bronc not go into rodeo sport?

Some bull riders, including Platt, feel as though their sport and livelihoods are disappearing, even though rodeos across the country still draw massive crowds. Platt blames it partially on a lack of training facilities where younger athletes can practice. But he also feels like there aren’t enough of him — people who love the sport enough to overlook its flaws and who can inspire the next generation.

“It’s not just a weekend sport,” Costello said. “It’s our life.”

No number of bones shattered or money lost can separate bull riders from their sport. They become addicted at a young age to the adrenaline of conquering the animal. Bigger arenas and heavier bulls motivate riders to climb back on, even if they risk a career-ending crash. They cling onto their dreams, desperate not to fall off, through those eight grueling seconds. Then, finally, a buzzer.