The oaks will remember

A widow watches over the haven for animals she and her husband built from bare earth.

April 18, 2025 | story by Tarryn Nichols

photos by Tarryn Nichols and Lauren Brensel

Mary Gregory loaded a golf cart with Southern live oak saplings that barely reached her shins. She was in her early 50s then, making countless bumpy trips across a barren watermelon field to plant saplings in the former crop rows. As each oak took root and began to grow, what was once a place without a single blade of grass steadily transformed into a sanctuary for aging horses, flocks of birds and other creatures in need.

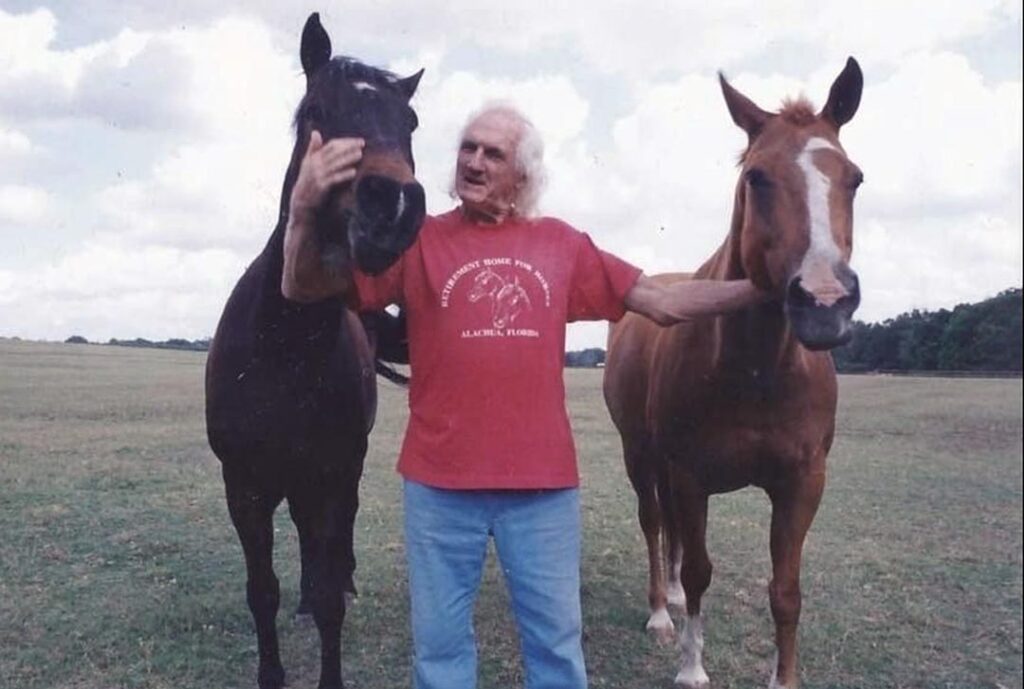

Those oaks are now massive. The 92-year-old who planted over 125 of them makes her daily golf cart rounds to greet visitors and horses under the ample shade they cast over the Mill Creek Retirement Home for Horses.

Mary and her late husband, Peter Gregory, purchased the parcel in 1983 and founded the farm the following year. Not long after, they started bringing in trailers of horses seized by law enforcement or frontline rescue groups who were elderly, abused or abandoned with nowhere else to go. The nonprofit venture is a testament to the pair’s shared devotion to nature that will outlast them as a refuge.

It lies north of Alachua, a sharp right turn off the heavily potholed County Road 235A. A wall of pines borders I-75 toward the front, muffling the roar of traffic before it reaches any horse’s ears. Namesake Mill Creek winds under three paved bridges, cutting through the middle of swaths of green pastures that stretch over most of the 335-acre property.

Beyond a dense buffer of trees, 50 acres of native woods and wetlands lie untouched by humans.

“I always say ‘Stay on my land –– you’re safe here,’” Mary said, gazing out at a flock of white ibises pecking at the marshy ground on the far side of a creek-fed pond.

Peter was also a founder of the Alachua Conservation Trust, a regional nonprofit that protects critical natural land from degradation. He donated the entire farm as a conservation easement to the organization to permanently preserve it for future generations of old horses as the surrounding area becomes urbanized.

Since its start in 1988, ACT has worked on the protection of over 66,000 acres of Florida land.

The couple built their home on the crest of the pond’s bank at the edge of the pastures, down a steep private drive hidden from visitors. A screened sunroom shades the patio where they ate vegetarian meals together, overlooking the water. A huge picture window in the master bedroom brings the seemingly boundless swampy landscape inside.

They used to chat in their Jacuzzi almost every day, but after Peter’s passing in 2014, Mary said she couldn’t bear to use it. Instead, she filled it with soil and planted a tree in the circular hole next to the pool. Bronze garden statues of dachshunds and other woodland creatures sit around the edge of the pool, like a preview of the house’s whimsical animal-themed decor.

Inside, it’s as if Snow White’s posse of critters –– deer, ducks, doves, frogs, turtles and of course, horses of varying size –– have settled on any bookshelf, coffee table and lacquered wood surface available. In spaces not claimed by trinkets, Mary has displayed memorabilia from her travels around the world. Sets of fine china gleam from glass cabinets, reflecting the glow of a nearby European floor lamp.

Despite the years spent curating her home, Mary prefers the peace and quiet of the outdoors.

“I love to sit out at the edge of the pond and watch all the wildlife. And I’m so lucky to think that they picked this place to come and walk up and down. Sometimes, at six o’clock, the pond will be so low, they’ll walk across it,” Mary said. “They come up out of the pond, walk up my bank here and put their noses on my screen. And I think ‘How can people shoot them?’”

She never disturbs the forest because it might cause the animals to flee onto neighboring plots, where they are no longer protected from hunters.

Mary spent her childhood in Hampstead, a wealthy London suburb known for its landscape architecture and educated liberalism. She was the only child of two reserved, nature-loving parents who spoiled the family dogs, Brutus and Cassius.

Mary said her father was a civil engineer who worked for the government during World War II. He never accepted a penny for his work in hopes he would be knighted –– but that day never came, she said. He was, however, later invited to the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II. The year was 1953, and Mary, then 20, got to attend as his plus-one.

As the war unfolded, Mary’s parents sent her to an all-girls boarding school far from home. She said the British crown donated a troupe of horses to the school, along with a royal horse trainer to teach the students how to ride. She was only 10 at the time, but her brown eyes crinkle with delight as she tells the story eight decades later.

The “war to end all wars” also still feels fresh in her mind. Many of the students’ fathers were enlisted, so the girls were kept from reading the newspaper to avoid the death notices. The boarding school, located in a quiet part of the country, escaped the air raids unscathed.

“If you had been in World War II,” Mary said. “You would never, ever want another war.”

Unlike her mathematics-minded father, Mary disliked numbers and dreamed of becoming a veterinarian. She enrolled at the University of London to study biology, which was difficult for women without an affluent male connection. Though gender discrimination kept her from pursuing her vet dream, university altered the course of her life.

She met Peter on the first day of class. They clicked instantly over their shared love for animals.

On the outskirts of the city, the young couple visited the Home of Rest for Horses (now The Horse Trust) a charity program that allowed working cart horses to retire. It was founded in 1886 by Ann Lindo, who was deeply moved by reading Black Beauty, a novel told through the eyes of a horse. Inspired by the idea, they made a promise to start their own animal sanctuary when they had the means.

On a chilly February morning, Mary wore a matted cream-colored fleece jacket patterned with pawprints and Cavalier King Charles spaniels that she’d bought when she founded the farm. A head of thinning pearly waves bounced under her ears, framing her leathery cheeks and deep laugh lines.

“I’m 92. I don’t feel it –– I just look it,” she said with an unhurried English accent.

After a slice of toast with coffee, Mary headed out on her forest green cart, the first of many drives to make as she feeds the farm’s 144 equines. Her chubby rescued dachshund, Mini, usually accompanies her in the passenger seat. When Mary’s not distributing carrots, she tends to her plants or clears leaves from a paved lane starting at the farm’s welcome kiosk. Further in, Mary’s Trail (named by Peter) carves a direct path along the creek to their house.

Her youngest son, Paul Gregory, rarely stops her because it “keeps her going.”

He previously gifted her two cordless leaf blowers, but –– knowing her stubborn nature –– made sure no one gave her batteries to operate them after she had eye surgery.

Paul described both of his parents as “tough people” who kept moving forward. His father was a fan of National Geographic, and Paul and his two siblings would travel the world with him, visiting locations they’d seen in the glossy pages.

All three Gregory children inherited Peter’s passions. Carol, the eldest, retired recently from her career as a travel agent. The second-born, Peter, shared the same name as his father and focused on protecting aquatic creatures like manatees and sea turtles. Paul said Peter “didn’t like leaving the water” off the islands of Islamorada, Florida, before he died from cancer in 2019.

Their father built his wealth as a hotelier, so the three children enjoyed an unconventional upbringing. Paul spent his childhood days playing in the ocean off the coast of Jamaica, near one of multiple hotels Peter built and owned before retiring in his late 30s –– over a decade before founding the farm. The family moved several times, living in tropical destinations from Portugal to Pompano Beach.

Paul, who calls his mother “Mary” out of respect, said she always preferred the warm weather.

The night Peter passed, Paul drove up from Fort Lauderdale and never returned to his job as a realtor. He meant to stay for two weeks, but this spring marks his 11th year on the farm. To his mother’s surprise, the 61-year-old former “playboy” assumed the role of president.

“It’s probably the best thing I’ve ever done in my life,” Paul said.

He wakes up at 4 a.m. to respond to emails, feed the animals and manage finances, all while handling a loyal team of eight employees and dozens of volunteers. There’s always a challenge for him to address, be it a fallen tree or faulty water trough filler.

“It’s all about the horses,” Paul said. “If you have two legs, you’re working all day long. If you’ve got four, you get to chill out and relax.”

The reward to the farm’s animals and visitors compensates for the job’s mental load, he said.

On Saturdays, Mill Creek opens to the public. Admission: two carrots. People often come in pairs, or with a gaggle of small children. Adults walk with an older parent on one arm and a bag of cored apples in the other. University of Florida students come to decompress after stressful exams.

Horses aren’t the only retirees people come to see. Mill Creek is also home to three donkeys, four rescue cats and a zorse – a zebra-horse hybrid mare named Tiger. Many of the elderly animals have health conditions that require special feed or medical attention, which adds to the $400,000 a year it takes to keep the farm running. Paul and his board of directors manage the grant funding, public donations and sponsorships that solely support these costs.

To the right of the crowded “Mane Concourse,” Mary watched an auburn-coated horse repeatedly roll on its back while gleefully kicking its legs in the air like a child, pausing to nuzzle its long neck in the grass. In Mary’s experience, horses behave like this when they’re comfortable.

Not one horse has ever left Mill Creek in its 40 years. Other farms may send horses elsewhere when they can no longer work or have high medical expenses, but Mill Creek is truly a forever home. The four-legged residents form strong bonds with other horses and humans until the day they are buried on the property.

A ghostly white stallion with an empty left eye socket sauntered over toward Mary with swagger, as if carrying the weight of his distinguished name — Homer — in every step. Along the same fence, a dark-headed endangered Sherman’s fox squirrel scampered across before disappearing into the lofty branches of a nearby oak.

Mary stopped her cart to read Homer’s laminated story, nailed to the aging wood across from Essex Field. The South Florida Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (SPCA) rescued him from an abandoned nursery full of trash, where he had no food or water to drink. He was blind in one eye, lame in his front leg and very fearful of humans.

“But he wasn’t with me,” Mary said, joking that she wouldn’t sleep that night because she had no carrots to give him.

Each time a new horse arrives at Mill Creek, Mary gently greets it at the front gate. Some traumatized horses allow only Mary to touch them at first, but she’s always amazed by their capacity for forgiveness.

“I’m a human being just like the one that’s been so mean to them,” she said. “If you had been ill- treated by a human being, you’re not going to come and let them do that sort of thing to you.”

Both she and her son wish the state’s justice system were more effective when it comes to punishing offenders of animal abuse. Since the farm was founded, animal welfare laws have not improved much, especially when it comes to horses. Even active police or military horses rarely have a place to retire in peace after their service, Paul said.

Offenders of aggravated animal cruelty, meaning repeated intentional torture or neglect of an animal, may be sentenced to a maximum of five years in prison or charged a fine of up to $10,000.

“I feel like they should have people go through what they put an animal through,” Paul said.

Paul has no children of his own to take over his role, but he and his sister, Carol, work together on the board of directors to make important decisions regarding the farm’s future. Other board members began as dedicated volunteers. Together, with a crew of long-serving employees who handle day-to-day operations, they have the expertise to keep the farm running in case anything happens to the Gregorys.

One of those volunteers is Kevin Sheehan. He described Mary as “down to earth” when it comes to both her humbleness and how she loves her land and animals.

He first met Mary while working at a Publix in Gainesville over 40 years ago. She was carrying a curiously large bundle of carrots, so he had to ask about them while helping her out to her car, he said. The exchange led him to start visiting the farm with his family, where Mary later let him host his daughter’s childhood birthday party.

Upon retiring last year from his management position, Sheehan sought her out to become a volunteer. Painting fences and tending to other maintenance tasks was a welcome change of pace for the self-described “city slicker.” Every day, Mary earnestly thanks him for his work.

“How do you buy this land with a vision of making it into a horse farm with just grass?” Sheehan said. “They had to plan everything from scratch.”

Mary doesn’t feel a need to leave the property, except when Paul occasionally takes her to dine at a restaurant. Nowadays, there are more mainstream vegetarian options on the menu. She and Peter always ate at home: There’s no restaurant in Alachua where you can eat and watch horses at the same time, he would quip.

Peter’s grave lies in the Field of Dreams, a memorial park lush with live oaks and flowering trees in the eastern corner of the farm. An oak is planted in honor of every horse who reaches the end of its life at Mill Creek. In time, Mary wishes to join them.

“I want to be buried on this property,” she said. “Way out, where no one can see.”