For half a century, the University of Florida’s mascots were living alligators. The story of the original Alberts shows the depth of human cruelty to animals — and how we can change.

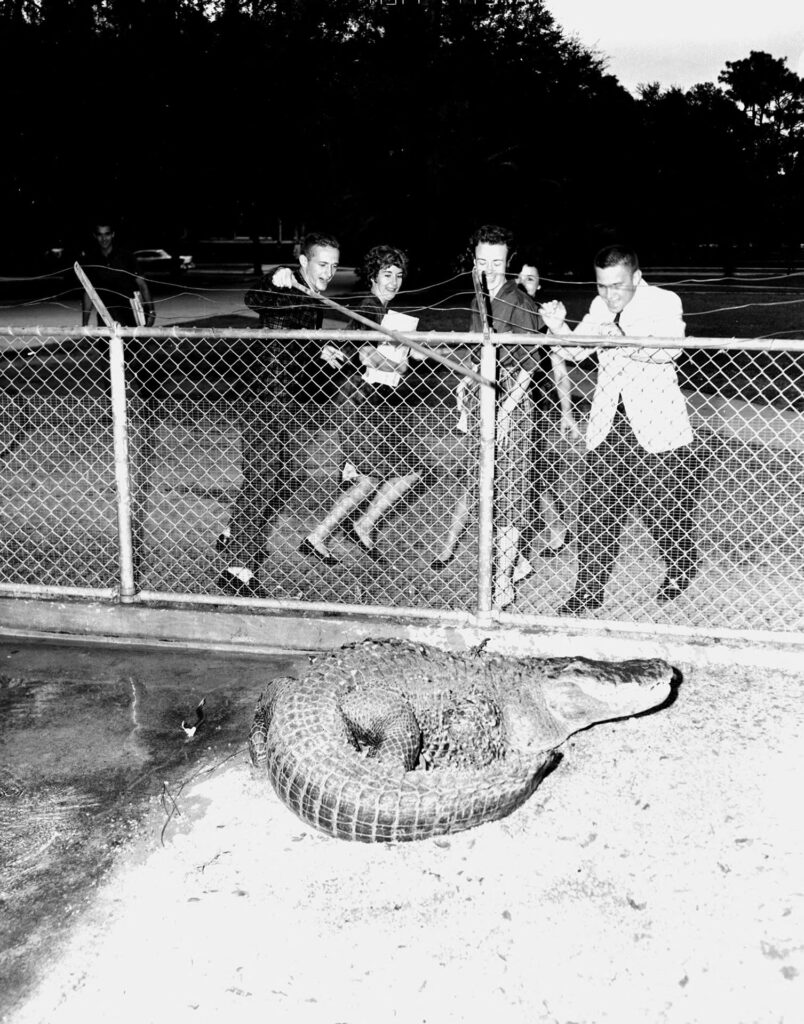

UF students surround their living alligator mascot, Albert, in his campus pen in 1957. (Courtesy of University of Florida George A. Smathers Libraries.)

October 19, 2024 | story by Sarah Henry

In January 1954, a moonless night settled over a small college town in the swampy heart of Florida. The University of Florida campus in Gainesville was quiet, its dorm rooms mostly empty awaiting winter break’s end. But morning at the Sigma Phi Epsilon fraternity house brought a bloody discovery.

Not far from Lake Alice, an on-campus oasis for both students and wildlife, lived Albert the Alligator, UF’s live mascot. Albert’s home was not the lake or its marshy shores but the SigEp backyard. Albert spent his days in a chain-link pen, his only oasis a small, muddy pool.

Lent from the Ross Alligator Farm in nearby Silver Springs, Albert was 10 years old when he made his debut at the Florida-Georgia Tech football game in the fall of 1953.

That winter, while students emptied campus for the holidays, Albert waited alone for the next game where he would be lugged in front of a stadium full of cheering fans. He was the embodiment of UF school spirit but also the target of its rivals. He was often painted and doused in alcohol, historic news clippings show — abuse that masqueraded as game-day antics.

Upon returning from holiday break, SigEp member George Hapsis, “guardian of the beast,” went to check on his gator brother. “I went over to the pen and found Albert sprawled on his back in his almost-empty pan of water,” he told The Special Alachua County Journal in 1954.

Albert had been beaten to death.

A funeral procession, white-brocaded casket and Gator Band trumpeter sent Albert to his grave at the heart of campus beneath Century Tower, a 157-foot-tall, gothic-inspired bell tower then still under construction.

“He may even float upwards and serenade the silent campus with a doleful dirge on those dadblasted bells while searching the landscape for his assailant,” wrote student Gene LeGette in the student newspaper, The Florida Alligator, envisioning Albert’s ghost.

Ten years later, early on a Wednesday morning in November 1965, another Albert lay unnaturally still in his pen. This time, Albert had a small bullet hole below his eye. His attacker was nowhere to be found.

Lester Melvin, Albert’s caretaker, used a stick to feel out the wound, which went almost straight through the gator’s head. “It’s a pretty sick person who would do something like this. Somebody’s always tormenting the alligators,” he told The Florida Alligator. “Why didn’t people just leave him alone?”

Melvin raised a good question. From the early 1900s until 1970, a long line of live UF alligator mascots were subject to unending abuse. After a bad case of lung worms, two murders, and two gator kidnappings involving a Florida State University flagpole and a Miami hotel room, UF’s student government voted to demolish the gator pen. At the rise of the environmental movement not long after the first Earth Day, student activism helped send the last of the Alberts back to his swampy roots.

Far beyond football season, UF’s living mascots reflected the human relationship with alligators, whose populations were then plummeting across the south. The flagship university’s gator mania against the backdrop of its gator mistreatment — abusing the very symbol of its strength — reveals how we can at once love animals and do them harm. Just as crucially, the Albert stories show how we can change our relationship with the animals that share our world.

Natural History

At sunset, the banks of La Chua Trail at Gainesville’s Paynes Prairie glimmer like wet stone as dozens of gators bask in the last of the day’s warmth. Children skirt around them, testing the limits of their parent’s warnings. When night falls, the hunt begins — the alligators slink into the water, bright eyes shining from behind switchblade grasses under canopies of stars.

Before European colonists settled in southern swamps, alligators reigned supreme. At the top of the food chain, the American alligator is a keystone species that holds together the ecosystems it inhabits, said Mark Hoog, an alligator researcher at the University of Georgia’s Marine Extension and Georgia Sea Grant.

It’s a role they’ve played for many millions of years.

When an asteroid hit Earth at the Gulf of Mexico around 66 million years ago, triggering an apocalypse for the dinosaurs, crocodylia, the order of reptiles that alligators belong to, managed to survive.

The first true alligator species, Alligator prenasalis, came on the scene around 37 million years ago in what is now the Great Plains. Since then, alligators have changed very little, said the reptile paleontologist Evan Whiting. By at least 18 million years ago, alligators had made their way to Florida.

“Alligators are one of the most resilient animals there are,” Whiting said. “They’ve survived multiple episodes of major climatic changes.”

Only one threat came close to sending them the way of the dinosaurs.

“People have pushed alligators closer to the brink than anything else in their evolutionary history,” Whiting said.

“Gator Tales”

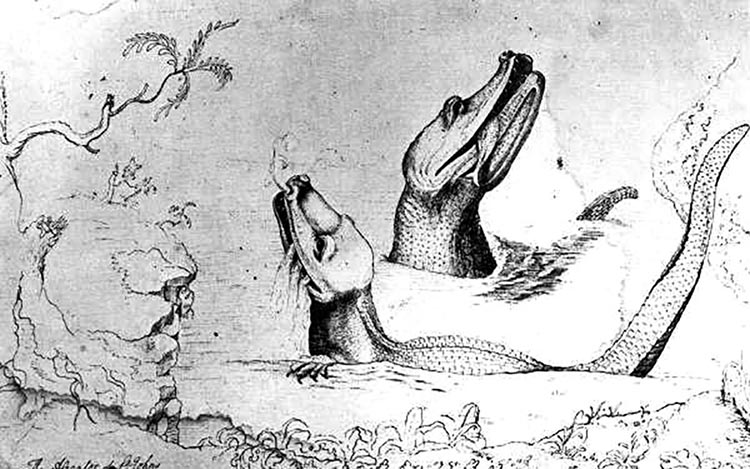

William Bartram’s drawings of alligators on Florida’s St. Johns River, published in his Travels of 1791, also exaggerated their ferocity, even depicting smoke rising from their nostrils. The popular book helped influence early American ideas of alligators as monsters. (Courtesy of State Archives of Florida)

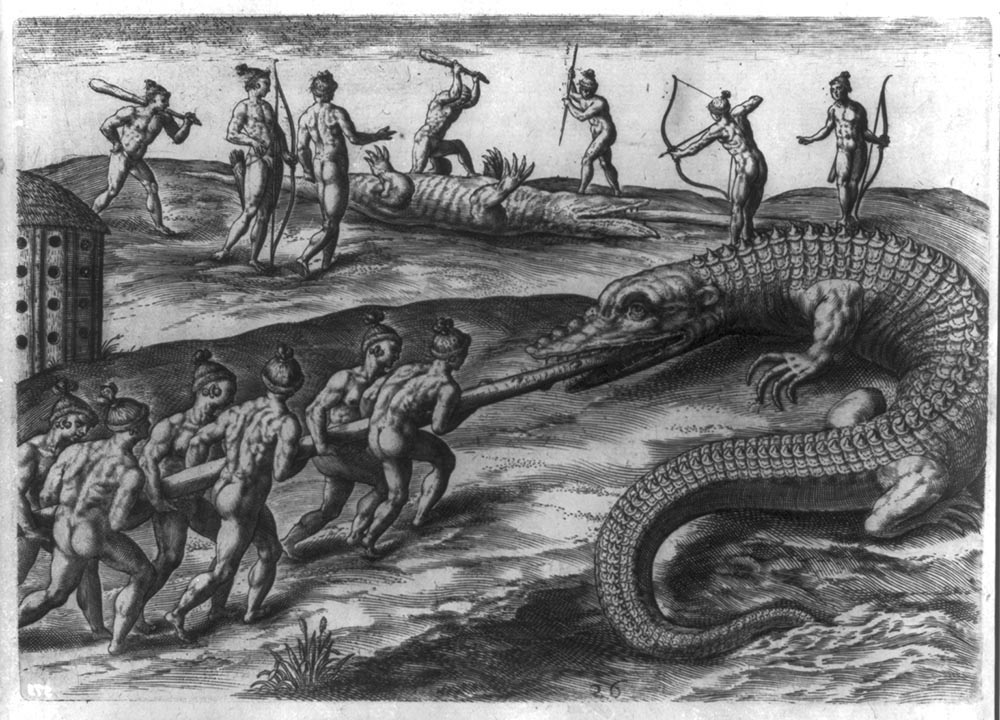

Alligators have long been valued for their inky skin, chicken-esque meat and pointed scutes that armor their backs. The French artist Jacques Le Moyne, a member of the Fort Caroline colony, painted exaggerated scenes of Native people hunting and roasting them in what is now Florida in the 16th century.

Naturalist William Bartram wrote about alligators in his Florida journals as early as 1774. Like Le Moyne’s paintings, Bartram’s Travels embellished the animal’s size and ferocity.

“That book became very influential in how people think about the alligator,” even if its depictions may not have been entirely truthful, said Mark Barrow, a history professor at Virginia Tech who is working on a book about alligators.

Barrow said that Bartram confused the gator with its crocodylia cousin, the Nile crocodile, notorious in ancient Greek and Roman texts for its dangerous attacks.

Still, Bartram’s book laid the foundation for a sensational body of alligator beliefs that would define public perception in the centuries to come.

To Bartram, Barrow said, alligators were “man-eating monsters.” In the centuries since, they’ve come to be known by many other names: swamp puppies, murder logs, Florida dinosaurs and most familiarly, gators.

When Florida became a tourist destination in the 19th and early 20th centuries, visitors would throng around dirt pens to watch gator wrestlers locked in a man-versus-nature battle that would increasingly define the gators’ story in the state.

In the 16th century, the artist Jacques Le Moyne, a member of the short-lived French colony known as Fort Caroline, painted exaggerated scenes of Native people hunting, killing and roasting cartoonishly large alligators in what is now Florida. Engraver Theodor de Bry later published this and other Le Moyne paintings, popularizing the images across Europe. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress.)

As an early emblem of wild Florida, the southeast’s last frontier, gators came to symbolize brute strength and swampy mystique. Everyone wanted to take a piece of them back home.

Businesses sprang up around gatormania: gator hunting, gator wrestling, roadside gator jerky, live baby gators in gift shops. Stories, too, became valuable souvenirs — traded at roadside dives in the thick of the glades and back home after a Florida vacation.

UF’s young football squad took on the gator as its mascot in 1908. The team had a live alligator mascot as early as 1922, according to historic newspapers, and dragged it to out-of-state games in the northeast in even the coldest months. That year, players brought their reptilian mascot on a November trip to the nation’s capital, visiting the White House and meeting President Warren G. Harding before traveling on to Cambridge for a game against Harvard.

It wasn’t until the 1950s that the live gators were dubbed Albert, perhaps inspired by a famous alligator in a popular comic strip at the time. The Walt Kelly comic Pogo featured a troupe of anthropomorphized swamp-dwelling animals, including an alligator named Albert. Syndicated from 1949 to 1975 and read by 37 million Americans in 450 newspapers at its peak, Pogo often tackled serious issues in satire, according to natural history writer Matthew Wills.

It was Pogo who took a famous lament and applied it to the environment: “We have met the enemy and he is us.”

It could have been said about mid-twentieth century Florida.

On the Brink

By 1957, Albert’s pen was outside UF’s bell tower. It was littered with concrete blocks, cigarette butts and the gold and red labels of Schlitz beer cans. His torment was two-fold: the endless dumping of trash and the endless taunting from the students he represented.

Student Body President Eddie Beardsley published a plea to his constituents in The Florida Alligator that fall:“What the hell is wrong with people around here?” he wrote of the students who tied razor blades to long sticks to cut up Albert’s belly and who tried, in vain, to poke out his remaining good eye.

Another Albert was nicknamed “Stumpy” after his tail was cut off by gator-nappers who then held him captive.

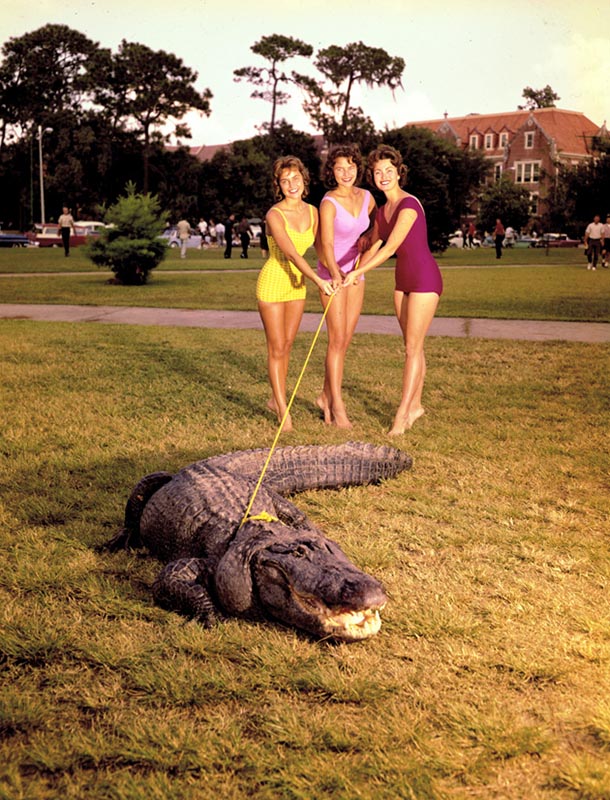

Three UF students in the Plaza of the Americas pose with mascot Albert the Alligator in the 1960s. (Courtesy of University of Florida George A. Smathers Libraries)

In the 1960s, three football players were put on probation after they were found lurking in Albert’s pen with a hatchet. Halfbacks Dick Skelly and Bob Hoover admitted to an ill-fated bet about who could wrestle the gator and pin him down for three whole minutes. Their penalty placed the fate of the 1961 football season in question and caused statewide outrage —- not over the harassment of the alligator but over the suspension of star players.

While UF’s gator mascots suffered, alligator populations across the southeast plummeted under other kinds of harm. Bartram’s “man-eating monster” could not survive pollution, the thriving hide business or burgeoning development of their habitats. The apex predators became luxury purses. Their swamps became our subdivisions. They went sterile from decades of DDT poisoning.

From Louisiana to Florida, alligator numbers dropped below 90 percent of traditional populations — so low that many scientists predicted they would never recover.

Pollution from insecticides caused hormone disruption in gators living in Lake Apopka, one of Florida’s largest lakes. UF’s own Lake Alice was choked with water hyacinths, an invasive aquatic plant feasting on excess nutrients from sewage dumping.

A reptile that managed to outlast the dinosaurs during the last great extinction event appeared unable to survive us.

Roaring Back

The first state protection for gators came in 1943, with a statute outlawing harvesting of alligators under four feet long. Nineteen years later, a federal mandate banned alligator hunting outright. In 1967, alligators were listed as threatened under the first version of the Endangered Species Act.

A new environmental ethic was rising across Florida and the nation. In 1970, the UF student speakers bureau ACCENT agreed to host a major environmental event, “Tomorrow in Perspective” for the first Earth Day. An estimated 3,500 people packed the old Florida Gym, nicknamed “Alligator Alley.” Come football season that fall, UF Student Body President Steve Uhlfelder wrote a letter to the university’s president asking that the latest living Albert be released, and its pen permanently removed to halt a legacy of mistreatment and cruelty.

“I’m sure Albert would be happier in the outside world,” Uhlfelder said.

UF President Stephen C. O’Connell agreed to talk with experts, including zoology professor Archie Carr, to figure out whether keeping a captive Albert was inhumane.

“He should be removed before football season,” Uhlfelder told The Florida Alligator, “which is generally when he gets the most abuse.”

And he was.

Visitors to the UF campus poke Gator mascot Albert with a stick in 1960. (Courtesy of University of Florida George A. Smathers Libraries)

That November on a bright autumn afternoon, Florida wildlife officers carried the last Albert away without ceremony — back to the lake, to the catfish and bluegill, the egrets and osprey. At 2:22 p.m. Albert sank below Lake Alice’s surface, the dark, ancestral waters reflected in the slit of his eyes.

It was not the end of Albert the Alligator but rather, the beginning of a new tradition fashioned from vinyl and leather, foam and fabric.

It didn’t take long for a student mascot to emerge and fill the claw marks the real gators left behind. During the fall ’70 football season, Phi Gamma Delta brother George Luttrell walked onto the football field in a cartoonishly animated alligator suit to a stadium of roaring fans.

It was hot. It was hard for him to move around. But it was his choice.

On campus, gators no longer lived in a pen. Under federal law, they were protected from hunting, and then from the insecticide DDT, banned in 1972. By the late 1980s their populations recovered to the point that the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission began reintroducing hunting through its statewide permitting program.

The alligator was hailed one of the Endangered Species Act’s first success stories. In 1987, the same year they were taken off the endangered species list, the legislature named alligators Florida’s state reptile — a reconciliation prize for being brought to the brink of extinction.

But a dark and scaly underbelly to their conservation history remains.

Living With Alligators

Alligator populations in Florida have increased by nearly sixfold since 1974, when their numbers fell to around 400,000. Now, they’re found in swimming pools and neighborhood canals, skulking on golf courses and sunning on a stretch of I-75 through the Everglades, the highway known as “Alligator Alley.”

Our reptilian neighbors have become so numerous that FWC has an entire arm dedicated to “nuisance” alligators. The Statewide Nuisance Alligator Program (SNAP) fields calls from concerned residents who worry an alligator has gotten too big, too comfortable or too close.

According to FWC, over 8,000 nuisance alligators were trapped in 2022 alone.

Concerns about alligators are not unwarranted, as the heartbreaking death of a child at a Disney World lake reminded the world in 2016. Large alligators can prove dangerous to people and pets. But biologist Ryan Ford with the Florida Fish and Wildlife Research Institute said they are likely more afraid of us than we are of them.

Alligator bites on people have seen a slight uptick over the past 40 years. But it’s not because they are hardwired killing machines, Frank ‘Gator’ Robb said. An alligator trapper and researcher, Robb instead blames Florida’s sprawling development.

“A lot of the wild areas we have are being built up,” he said.

In 2022, Florida was the fastest growing state in the country. Southward migration brought 1,000 new residents a day to suburbs built on former wetlands. That encroachment on the remaining wild spaces puts people in closer proximity to alligators, Robb said.

With around 10,000 nuisance calls a year, Robb also believes that some are from people who just aren’t used to living beside gators.

“A lot of people move in from out of state and have never had interactions with gators before,” Robb said. “Sometimes, it makes them a bit quicker to panic.”

Much like Bartram’s “man-eating monsters” of centuries past, the biggest threat to gators these days may be public perception, Robb said. Tampa trapper Phil Walters agrees.

Walters caught his first gator in the 1970s, long before he would become a contracted nuisance trapper with FWC. At age six in the backwoods of north Tampa, Walters said he wrestled a 4-foot gator into his family’s bathtub. Now a retired salesman, he does something similar for a living.

When SNAP receives a call from a concerned resident, operators first determine whether the gator is a threat. If so, they issue a permit and call up a trapper. If Walters gets the call, he drives out to the site and sets up a trap: beef lung, because it floats, hooked to a jumbo rod. He waits. Hours sometimes, days others.

In Hillsborough County, the alligators that Walters traps are of the backyard variety — those with homes in neighborhood lakes and canals surrounded by manicured lawns. Most trapped nuisance alligators are not relocated but killed.

Gators over 4 feet almost always try to return to their home, and on the way back they can cause problems for people and other wildlife, said Lauren Claerbout at FWC’s Division of Hunting and Game Management.

“When a contracted nuisance alligator trapper removes an alligator, it becomes the property of the trapper,” Claerbout said.

“It’s up to the trapper to figure out what he’s going to do with the thing,” Walters said.

For him, there’s little incentive to sell gators alive to zoos or farms. Walters makes just $50 per gator from FWC. Most of his profit comes from selling them for their meat and hide or as trophies.

Keeping Your Enemies Close

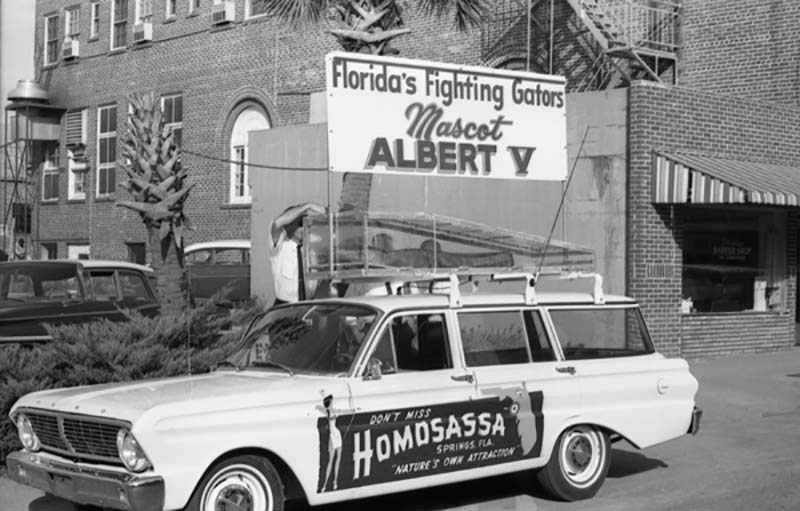

A living UF alligator mascot being transported through Tallahassee in 1965. The sign reads “Albert V,” indicating the fifth Albert. But historic news clippings show that UF’s football team traveled with live alligators since at least 1922, suggesting many more live alligators served as official and unofficial mascots for half a century. (Courtesy of State Archives of Florida)

Looking back over the history of alligators in Florida, Dr. Anna Peterson, a UF professor specializing in environmental and animal ethics, said our ability to mistreat them while holding them up as our mascots is unsurprising.

“It’s part of a larger total cognitive dissonance,” she said. “People’s attitudes towards non-human animals are really complicated and often contradictory. They often don’t really make scientific, intellectual or moral sense.”

The alligator’s story is not unlike that of the American Buffalo, which faced extinction near the end of the 19th century due to westward expansion by early colonists. The buffalo also became a symbol of American freedom, all the while being decimated. In 2016, it was officially named the country’s national mammal.

In the animal anthology “Beastly Natures: Animals, Humans, and the Study of History,” Barrow writes, “the alligator has become a kind of semi-domesticated reptile subjected to intense human surveillance, manipulation, and intervention.”

Peterson wonders how our attitudes towards alligators, and wild animals in general, make that manipulation feel justified.

“The whole idea of the managed hunt and the whole idea that an animal can be a nuisance when it’s just living in its own historic habitat is just a result of human encroachment,” she said.

As development amps up along coasts and into swamps, alligators might fall prey to what the Georgia alligator researcher Hoog calls “local extinctions.” The threat, he said, is not a mass endangerment like the one they faced mid-20th century, but a hyper-local decline with cascading effects.

“Alligators are what we call ecosystem engineers,” Hoog said.

By digging gator holes and building nests, they provide habitat for neighboring reptiles and amphibians without which those creatures suffer or move away.

Gators are an integral link in a larger web of connectivity of which we are also a part. We come from the same place: tannic rivers, sawgrass seas, Spanish moss and sun-soaked days.

Today, UF’s gator mascots — Albert E. and Alberta — are played by students suited up in plush, roomy costumes cooled by a battery-powered fan, rather than the stifling vinyl and leather suits of the ’70s. But the ghostly memory of UF’s living mascots can still be found on campus.

At the Florida Museum of Natural History, a mile southwest of Lake Alice where the last of the Alberts was released into the wild in 1970, an alligator skull sits behind plexiglass. The large, bleached-white skull belonged to one of the last caged Alberts. No longer harassed in pens, dozens of alligators nicknamed Albert endured some harassment at Lake Alice for many more years, gobbling marshmallows and other human items pitched at them.

The 12-foot alligator died at UF’s medical school after an X-ray revealed a glass bottle in its large intestine, blocking the digestive tract.

Cracked and pock-marked, the skull is a reminder: Alligators are more than symbols we use to make meaning of our own identity. They are wild animals. Their ancient bones are embedded in the limestone we build our futures on.

They existed long before us, and their resiliency shows they could survive long after.