A teenager’s admiration turned into grief

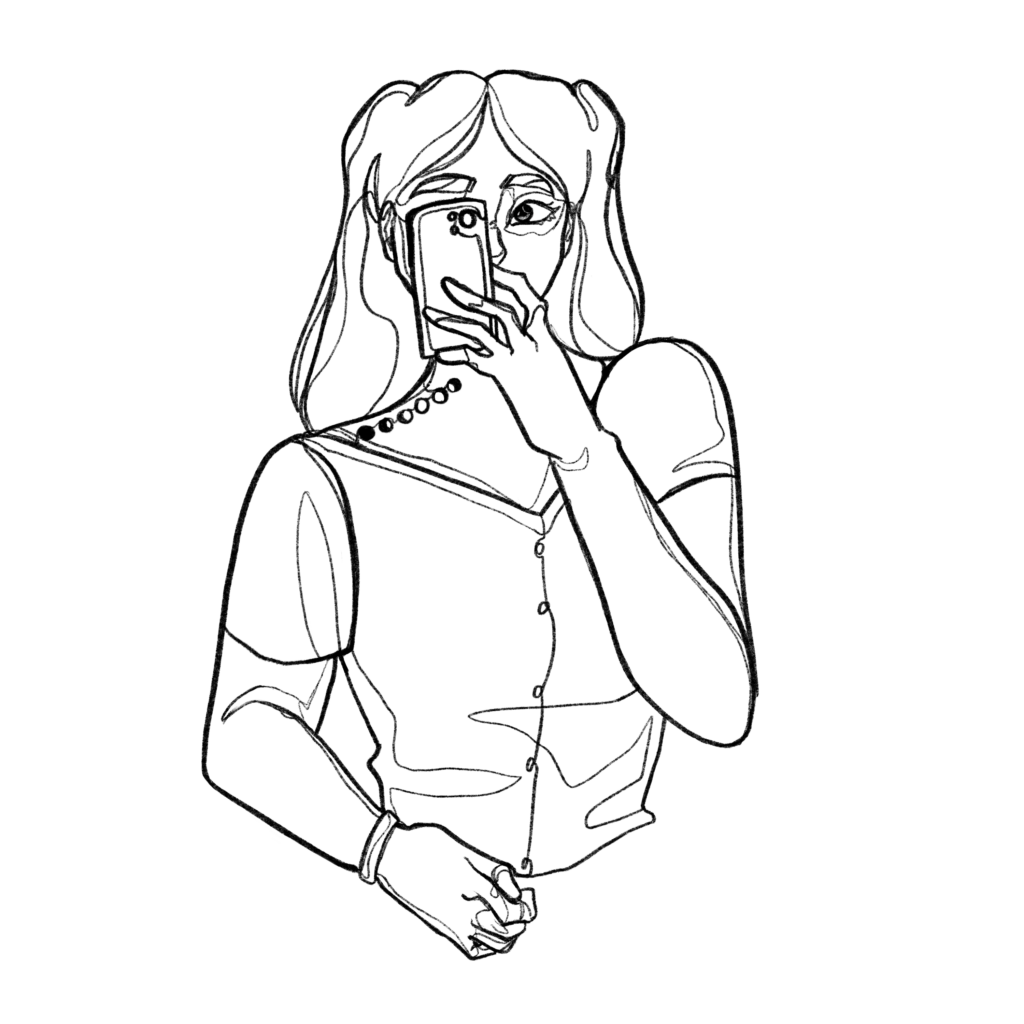

An illustration of Kayla posing for an Instagram photo, showing off her phases of the moon tattoo. She loved anything witchy and astronomical.

April 19, 2023 | Story by Allessandra Inzinna | Illustration by Delia Sauer

2021

I set my phone to a heartbeat vibration a week before I got the call. Instead of a few long buzzes, my phone would erupt in quick, irritating pulses. I hadn’t received many phone calls in that time, and the ones that did come through startled me into answering.

When Suzy, a high school friend I had long since lost contact with, called, I still hesitated. It rang. And rang. I paused a YouTube video on dissecting the family dynamics of the Sister Wives and picked up the phone.

We caught up briefly. She served drinks down on South Beach and recently broke up with her boyfriend. I was in my second year of college, writing for a local newspaper. It all sounded fine. The tone of her voice seemed tight.

When we reached the end of our obligatory catch-up, she asked, “Do you remember Kayla?”

I thought of my hip, where Kayla haphazardly tattooed a lopsided mountain with an inked sewing needle tied around a pencil. I wondered if she had worked on pulling straight lines.

“Of course I do.”

“Yeah, um…” She sighed. “She’s dead.”

I had never felt my mind go blank before. I might have enjoyed the absence of thought in any other circumstance.

“What?” I jack-knifed upright. “Are you joking?”

I could almost hear the shake of her head, the teeth on her lip.

“No.”

2017

Kayla held her box braids in a fist, flipped the bundle of them over to one side. She was so different then. Supple, even-toned, rebelliously stamping the earth with her combat boots.

Kayla existed a degree apart from me. She was my sister’s friend, first and foremost. But my sister’s group invited me into their fray in my sophomore year — and their senior year — of high school. Liz had the master bedroom of every house we ever moved into, a sort of apology from our parents for moving her around so much. We all hung out there throughout the week.

“Guys,” Kayla whined in my sister’s room. “How do I look?”

The room echoed “you look great” and “beautiful.”

Her Tinder date waited in my driveway. I could picture my mother glaring out a window at the strange man in the Ford truck. I was sure Liz made up some excuse, like that it was just her father picking her up. I’m sure he had the frown lines of a father.

I loitered shyly in the doorway, weathering a stab of jealousy. Her heavy black eyeliner, the Daisy Dukes shorts, the ill-fitting tank top that erred on unflattering. She hid a tongue piercing behind bleach-white teeth. I wondered how a person could look so exactly like themselves.

Kayla stepped past me on her way out with a wispy “bye, see you later.” If chrome could walk, it would walk like her. Bouncing, yet sure-footed. She faded into a stranger’s passenger seat. I saw nothing wrong with this picture. I found it all exhilarating. I found Kayla exhilarating.

“I really like Kayla,” I admitted to my sister later.

“Why?”

“She’s self-possessed.”

“I don’t think so,” Liz said, refusing to elaborate. “I don’t think so at all.”

That night, I posted on my private Instagram with the caption: When I get older, I’m going to be pierced and tattooed, and no one is going to recognize me.

“I’m going to hang out with that guy again,” Kayla said.

My sister hummed. Liz, Kayla and I were out on a walk around my house before dinner. Food tastes better to the intoxicated tongue, apparently. The thought of smoking anything made me dizzy. Nonetheless, I helped scout a hideout.

“He invited me over to do Xanax.”

I, as usual, was an observer. I had ingrained myself in their friend group just enough to quip about the smaller subjects: disappointing men, teachers we collectively hated or loved, whatever supposed nonsense our parents pulled that week. I had no footing on the grounds of this conversation.

“Why?” Liz asked.

“Because I like them,” Kayla said.

“I don’t think you should do that,” Liz continued. It was a strangely easy capitulation that I didn’t understand at the time.

What I did know was that I was curious about the “them” Kayla spoke of, not the “him.” I thought I would like them, too. I would like the numbness, the droop of my eyelids, the absence of that simmer charring my lungs those days.

In high school, my insides squeezed with anxiety every minute. Sleep was my only respite. And when I woke up, my thoughts raced cyclically, obsessively. I know it now as obsessive-compulsive disorder. Then, I didn’t know what to do or how to stop it. Weed made it worse. Alcohol made me stupid. I didn’t have easy access to anything else. I just endured.

But Kayla had a clue. She figured out how to make it stop. I — naively, desperately — wanted her to teach me how.

Liz just shook her head. She had never been overprotective of her friends, only of me. She bodyblocked my attempts to sneak out and make midnight trips to the McDonalds on US-1. If it had been me planning a midnight getaway with some kid doing benzos in his mom’s basement, my sister would have slit his tires for even offering. With her friends, however, she showed disagreement in inches. A dissident sentence. An incredulous glare.

This seemed heavier. She knew something I didn’t. Maybe it was already a lost cause. It, not her.

2021

After our phone call, Suzy texted me details for a makeshift vigil she and a few others had planned. It was for Kayla’s high school friends. I borrowed my mom’s car and sat in it for an hour at the park, waiting. Suzy and a small group had stopped to pick up Domino’s. I tried to shake it off. People handle death differently. Some cry, some pick up a pizza and cheesy bread.

We settled on a picnic table, where they spread out their assortment of snacks. The bay lapped against the rotting wood of a nearby dock. I felt nauseous as the breeze wafted molten mozzarella.

We spoke about our last sightings of Kayla. The last time I had seen her was months ago, and she was in a waking coma.

I relayed the scene at the vigil — me, sitting on Suzy’s couch during a party, feeling wildly out of place. One kid I went to high school with limped around the apartment with a bullet wound in his foot. When I asked him about it, he grinned and told me it was the trouble working in the trap.

And Kayla, oh God, she had lost all her baby fat. She wore a low-cut tank top, ill-fitting, over the line of unflattering. Her ribs poked through exposed skin. She sucked on a dead vape, unaware of its green blinking. She had stabbed a lopsided moon on the apple of her cheek with an inked sewing needle. She hadn’t gotten better at pulling straight lines.

I cautiously waved at her. She pulled up a chair next to me.

“How have you been?” I asked.

She stared back, deadpan.

“I’ve been.”

Back at the vigil, the wood of the picnic table splintered into my thigh. I told Kayla’s friends that I don’t believe in heaven. But I hope for it.

2022

Kayla’s here. Standing in front of me. We are somewhere suspended in powder blue and sunshine. It’s foreign but familiar. Her cheeks are full, and her eyes are sharp. Her hair is raked up into her signature space buns. She is the personification of chrome. I look at her, and I see everything I want to be reflected at me.

“Dude!” I fondly chastise. “Everyone thinks you’re dead!”

She shrugs, sporting a sly smile. I place my hand on her warm bicep, cup her baby face, squish her cheeks. She giggles and pushes me off. I want to make sure she’s real. She isn’t.

“Have you told anyone you’re alive?”

She shakes her head. That’s a problem, I think. But we can deal with it later. I pull her into a hug. I will later curse my brain for remembering her scent, her height, the tickle of her hair against my cheek, all so clearly.

“God,” I sigh. “It’s so good to see you.”