Another blue world

Florida’s springs support one of the nation’s most expansive underwater cave systems, but development threatens their future

February 6, 2026 | story by Marta Zherukha

photos by Marta Zherukha

Shane Paradis hovers in the water, motionless except for the twitch of a fin. If he doesn’t propel himself forward, he’s not going anywhere. It’s as close to zero gravity as he’ll get. Despite his three layers, the 72-degree water cools him as he swims.

His small flashlight, the only light source in the pitch black, illuminates an impenetrable wall. It was once jet black, but thousands of visitors have brushed their fingers along it, and parts have faded to white. Shane can only see as far as he turns his head. To his right, a thick cord leads him through an opening to the surface — if he chooses to use it.

The constant whoosh from his air tank, pumping with his breathing, fills his ears. Critters scuttle across the sandy floor; small fish dart past. All he can think about is his escape plan out of the cave. Strapped to about 250 pounds of diving gear, he doesn’t panic. Once he leaves, he’ll start thinking about diving again tomorrow.

Shane, 54, is one of the many cave divers who enjoy the 1,000-plus artesian springs in Florida. Florida’s springs are unparalleled for divers, renowned for their striking blue water and big caverns. Mystery draws them in: the chance to navigate something few people above the surface can. Discovery keeps them coming back.

The Sunshine State is booming with hundreds of thousands of new residents every year. As new developments embrace newcomers, pollution and water pumping put the future of Florida’s caves — and the sport of cave diving — in jeopardy.

A risky decision

Cave diving isn’t something people fall into. It takes thousands of dollars of gear, years of training and endless justifications to non-diving friends and family. Shane went diving for the first time in 2014, testing the waters of a swimming pool in the Dominican Republic. He spent about $200 the next day for a diving instructor to take him to a reef, and his life changed.

Shane was living in Brooklyn at the time — thousands of miles from the nearest cave. But he was addicted. Four years later, he got certified for overhead diving and could now swim in fully enclosed spaces with high-level gear. He started working as a dive safety officer at the New York Aquarium. In 2022, he said, he traded New York’s open ocean and shipwrecks for Florida’s dark, cold underground.

“It’s not an adrenaline sport,” Shane says. “You’re looking at wet rocks for hours. That’s kinda all you’re doing.”

His favorite wet rocks in Florida are in the Devil’s Spring System.

The system is half an hour from Shane’s house and well-liked by cave divers for its winding tunnels and clear water. Made up of Devil’s Ear, Devil’s Eye and Little Devil — named because they’re curved, circular and small — the trio is better known by the name of the park that owns the land: Ginnie Springs.

There, Shane finds an otherworldly peace.

Diving is not for thrillseekers. Divers must maintain a low heart rate and stay calm. They burn less gas that way. Many people who believe it’s an adrenaline sport lose interest in five years, Shane says.

“It’s not going to escape anything; it’s just going to be alone,” he says. “I mean, you know, nothing matters. You’re just there in this environment the Earth created, and you get to just look at it and just … be a part of it.”

It’s about keeping calm, he says. Staying focused can be life-or-death for divers. In other high-stakes sports, participants can stop if things get dicey. If a diver gets lost in a cave or miscalculates tank supply, there’s no easy way out. All risks lead back to gas, or its limited supply.

Going under

Despite the risks, Shane wants to spend the rest of his life cave diving. He’s struck by the beauty every time he gets back in.

“It’s not dissimilar to your first time being in water where you’re just taken by all of this new environment,” he says. “It’s just also weird, and you’re trying to navigate it.”

Samantha “Sam” Johnson, 27, is new to cave diving. She began in January 2025 and calls it the calmest extreme sport. Sam often went dry caving, exploring caves above the water table, for a while before she decided to pursue diving. Diving is much more complex, she says. Divers have their own kind of language. The community is hard to pass up.

When Sam dives, there are parts of the cave where she kicks hard against the flow, but she trusts her muscle memory. Each cave is unique, but dive training is universal.

Each swipe of Sam’s feet in the water was drilled into her by dive instructors. She navigates each cave with the comfort of the fish and critters who call it home. It’s basically her home, too. Her breaths are measured; she periodically looks at her wrist to check her oxygen levels and how long it will take her to decompress. Diving is a science in that way.

Ginnie is known for its clear water, but sometimes decaying leaves decorate the blue ripples, obscuring Sam from onlookers peering down past the surface. The light bleeding from the gaps of plant matter forms a mosaic of colors akin to Monet’s lilies, swirls of brown to green to blue. Sam doesn’t see that, though. She sees what her flashlight illuminates: jagged rock, sandy floors and built-in ledges where she and her buddies can review their dive plan.

“There are cave divers, and there are people who cave dive,” Sam says. “There are people who cave dive, and they get their certification, and they go maybe a few times a year … and then there are cave divers who are people that want to contribute back to the community.”

Sam considers herself a cave diver. She’s always loved volunteering and was involved in the conservation of dry caves. Florida’s underwater caves are even more precious to her, she says.

Sam sports a silver necklace in the shape of a cave arrow, plastic markers divers use to keep track of where they are in their journey. She’s considering getting the symbol tattooed when she becomes fully certified.

“I just got into these cave systems, and I said, ‘I want to help protect this,’” she says. “‘I want to give back to this.’”

Caves under pressure

Florida’s springs are abundant, providing freshwater for millions of residents and tourists to enjoy. The Devil’s Spring System, where Shane dives, is a first-magnitude spring, meaning it discharges an enormous amount of water. The system produces about 80 million gallons of freshwater each day, almost enough to sustain the city of Gainesville for four days. But more development and pollution jeopardize the future of the caves.

Nestlé, the world’s largest food corporation, is permitted to pump nearly 1 million gallons of water per day out of the Ginnie Springs system. Divers are concerned about how much is being pumped out of Ginnie Springs. But they still consider the spring system to be the best spot for cave diving in North Central Florida. They’re reluctant to publicly protest the owners of the springs for fear of losing access to their favorite diving site.

Environmentalists oppose the permit, arguing that the pumping could decline water quality and lead to water shortages. Activists like Our Sante Fe River, Inc. have boycotted Ginnie Springs in response to the water bottling permit.

As aquifer pumping continues, mainly for bottled water and agriculture, the risk for cave collapses grows. Florida’s caves are filled by the water table, and some then flow into the state’s rivers. Pressure from the water can help prevent the caves from collapsing and creating sinkholes.

Patricia “Pati” Spellman, a hydrology assistant professor at the University of South Florida, says heavy localized pumping could reduce the flow of the rivers they feed, changing ecosystems and threatening wildlife. The Devil’s Ear, one of the springs in the Ginnie system, is one of 30 Outstanding Springs, a first-magnitude spring with historic significance to the state. It’s one of 24 on the list with an impaired water quality.

All hope is not lost if Ginnie and Nestlé stick to pumping as much as their permit allows. Spellman says she doubts the company could pump so much that Ginnie would collapse. But pumping is just one challenge.

Developers in Florida are building apartment complexes, shopping centers and retirement communities on land above Florida’s aquifers — and the divers who enjoy them.

What divers think

Sam Johnson and Shane Paradis both volunteer for Karst Underwater Research, a nonprofit group that explores karst aquifers, or freshwater springs. The group collects water samples, maps tunnels and leaves guiding lines throughout new parts of caves.

Ken Sallot, a cave diver with KUR, says the group has access to research properties with sinkholes and caves that normal divers can’t swim in. It shares its data with scientists and conservationists.

Places like Mill Creek Sink in Alachua benefit from their research.

The entrance to the sinkhole that drops into a cave system is nestled behind a Sonny’s BBQ off Interstate 75. Through dye tracing, which involves putting an organic dye into the water to visualize flow, cave mappers discovered the Mill Creek Sink drifts into Hornsby Springs, about eight miles west, Ken said. Most of the cave system extends above the entrance and to the east. Areas of the cave rest under a Lowe’s Home Improvement, with some parts big enough to fit a multi-story apartment building.

In 2024, the Alachua City Commission approved a plot of 198 acres for houses and commercial plots to be built atop the Mill Creek system.

Ken warns there will be a host of problems as a result. Heavy equipment running atop the land weighs down the hollow ground and can cause vibrations that can weaken the rock below.

Natural water filtration could also be disrupted, he says. Dirt, soil and limestone act as a filter for storm water, sifting out compounds from fertilizer, pesticides and other agricultural and urban runoff.

Asphalt doesn’t work that way. Rather than acting as a filter, asphalt layered above works like a barrier. Anything that runs onto the asphalt — car oil and coolant leaks, pesticides from people’s lawns — will turn into big pools of chemical combinations ready to leach into the groundwater and infiltrate the aquifer. It could contaminate the water cave divers swim in and make drinking water unsafe, Ken says.

Ken started diving in 1994, and he says the water quality has deteriorated in the decades since. One of his favorite spots, Manatee Springs, has seaweed-looking algae covering the main headspring.

“That’s a sign of high nitrate levels,” Ken says. “It’s a sign of reduced flow. And it’s toxic.”

Most caves themselves have been left mostly unscathed for now. But as the pace of development quickens to accommodate new residents of the Sunshine State, divers worry that could soon change.

“People can’t see what we see,” Shane says. “But we see what happens when there’s a lot of agriculture around. We see what happens when there’s pollution, and we see it in our water because we see the effects. We see the effects of algae and how that affects the cave system. We see the effects on the animals.”

Divers like Shane and Sam map the caves to show how interconnected each spring is, trying to dissuade developers from building atop them.

“They just see the springs as, like, something they can advertise as part of whatever houses that they’re building … or they just completely plow over it,” Sam says. “I’ve seen some springs that just turn into ponds and [are] filled in or blocked off or trash thrown into it.”

Whether they’re involved with an exploration group, interested in conservation or obsessed with their sport, North Central Florida’s cave divers are committed to the future of their lifestyle for as long as they can have it.

It takes Shane about an hour to load the gear out of his car and walk it about 75 feet to the stairs, where he’ll get into the water and strap it all onto his body. It’s about 15 minutes longer than his descent will take.

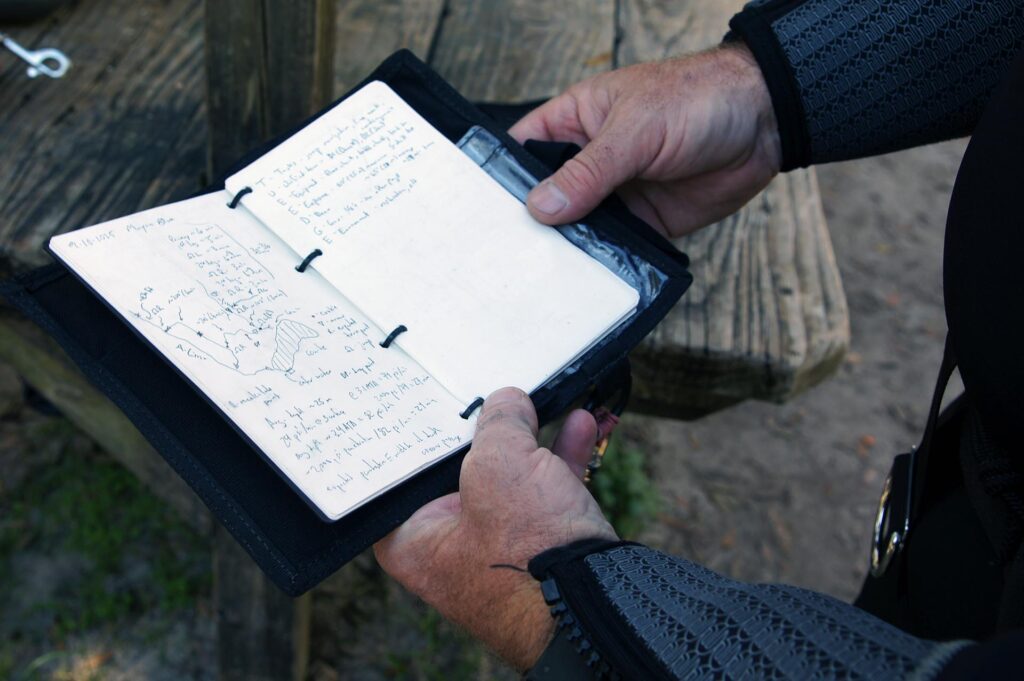

For one dive, Shane carries a cutting device, computer, gas, wet notes, spools, extra cutters, wrenches, tools, lights, extra bolt snaps, a spare mask, breathing hoses, stage bottles, a scooter and, of course, tanks.

An hour after setting the first steel tank out of his gray Subaru Forester, Shane sinks into the light blue water of Little Devil. “See you later,” he calls to the other divers at the spot, who laugh in a circle while they wait to climb the stairs out of their haven.

He starts his scooter, a 55-pound cylinder that propels him through the water at a meter a second, and he makes his way over to the Devil’s Ear as families in tubes float by. The water boils to the surface, spring flow rushing through logs and rocks to break up the flat, clear expanse.

With little more than a breath, Shane starts his journey.