The life and death of a

Florida abortion clinic

Fifty years after the first abortion clinic opened in a small college town,

the women remember where they came from, and where they are now.

February 19, 2025 | story by Siena Duncan

photos by Alissa Gary | illustrations by Delia Rose Sauer

This story is from Atrium’s Winter 2024 magazine, which released December 2024.

In 1974, Pam Smith knocked on a warm wooden door gleaming in the Florida sun. She wore a long skirt and a wrinkled peasant blouse, plus a few more obvious markers of a hippie during the decade: Birkenstocks and no bra (she hardly ever wore a bra). The morning breeze ruffled her long, stick-straight brown hair parted down the middle as another woman, older than her, answered the door. The older woman squinted, her eyes adjusting to the bright light.

“I want to work here,” Pam said.

“Oh, that’s wonderful,” the older woman replied. “But we don’t have any jobs.”

“I don’t care,” Pam told her. “I just want to be part of this.”

The woman gestured to the symbol on the door: a circle and a crossbow that symbolized Venus, the Roman goddess of fertility. It was a scientific marker for females and a harbinger of liberation, of pride — especially at the turn of the decade, when Jane Roe won a landmark court case.

The woman thought for a moment. “Well, three days from now, we’re going to have an evening where we’re all going to take a look at our cervixes. Have you ever done that?”

Pam shook her head.

“That’s OK. Just come on and join us. You’re welcome to show up then.”

Pam nodded, waving goodbye as the door closed. The boiling springtime sun reflected off the pavement in waves, and the heat threatened to overwhelm her as she thought about what could come next. Pam’s home was Gainesville, Florida, the small town cupping the state’s flagship of higher education, the University of Florida. She graduated with a degree in anthropology that took her 11 years and two kids to finish, and she didn’t know what she was going to do next. But a local building’s sign had called to her, shining in blocky handwritten letters: The Gainesville Women’s Health Center, coming soon.

It would be the first abortion clinic in Gainesville, and one of the first in the state since Roe v. Wade.

But even as women flocked to protest for the Equal Rights Amendment, striked for better wages and formalized the women’s movement with committees and conferences, the clinic would never grow larger than a single location.

Now, 50 years after its doors opened, abortion on demand is no longer a notion of the future; it is a thing of the past.

Restrictive abortion statutes have become common in Florida and other red states since the Supreme Court reversed the Roe v. Wade precedent in 2022. Just like after Roe, many cheered and many despaired — but for the opposite reasons this time.

The overturning unleashed new and old fights across the country. In the midst of protesters beating Bibles and counter protesters screaming for women’s rights, Florida asked voters whether they want to reverse its six-week abortion ban with a constitutional amendment.

After two years of fierce debate, 42.8% voted for history to repeat itself, for better or for worse. The amendment needed a supermajority vote to pass. The current six-week ban on abortion stands.

The issue has transformed since Pam knocked on that door 50 years ago — for her, for the women who came after her and for me.

BYLLYE

Before Roe v. Wade’s ruling, Florida employed a total ban on abortion, with little exception. Nurses like Byllye Avery struggled when pregnant women came into hospitals with wringing hands and desperate eyes, searching for answers. She’d often attempt to connect them with priests she knew in New York, who could get the women to surgeons. The journey was a pilgrimage to a mecca where abortion was legalized — health officials estimated about twice as many out-of-state travelers received abortions in New York than actual residents. In total, nearly 400,000 abortions were carried out in two years. Hawaii, Washington and Alaska passed similar laws, but travel from the East Coast was far more expensive, and the laws required people to live in-state for a period of time. New York was the only option.

Byllye worked at Gainesville’s Shands Hospital, the university-run medical facility. It was the largest healthcare option for many of the rural counties surrounding the city and still is today. She directed many women to make it to New York. But there came a day when one sat in front of Byllye and shook her head — a Black woman like herself. She couldn’t afford the travel, she said.

Byllye told her she was sorry, but she couldn’t help her at Shands. The woman nodded and left.

A few weeks later, she learned the woman died from a self-induced abortion, Byllye said.

Her face was frozen in Byllye’s mind for a long time afterward. She was there when Byllye read that Norma McCorvey, known to the world as Jane Roe, took her civil case against Texas statutes banning abortion all the way to the Supreme Court. She was there when the world announced that Roe had won. She was there when the Alachua County Medical Society denied Planned Parenthood a clinic location in Gainesville, and still, Byllye had to send women on the road to find care.

After the Roe v. Wade ruling, Byllye sat down with her fellow nurses and decided that they wouldn’t tell another woman no. They would start an abortion clinic in the city.

“We didn’t ask permission,” Byllye says, her voice warming. “We just did it.”

They rented out a vacant building made of faded brick. Doctors’ offices at the time were typically a drab gray, with few decorations on the walls and stark-looking metal chairs in the waiting rooms. Given the chance to design an office of their own, the women took it upon themselves to give the building a makeover.

They laid down sea-blue shag carpeting over the cold tile in the waiting room. They bought couches and chairs and coffee tables from JCPenney. They spread paintings and tapestries over the walls. They painted those walls brighter. They bought lamps to spread warm light across the waiting and recovery rooms — an especially important touch, considering abortions would occur at night a few days a week to allow working women a chance for discretion. And instead of hospital beds, they bought recliners.

To get the money for the machines as well as the decor, the women maxed out their lines of credit with the hospital’s credit union — $2,000 per employee, worth around $13,000 today. Byllye bought the couch and chairs in the waiting room from her own pocket. The patient gowns were handmade, stitched with care. It was about the women, Byllye said. It was always about the women.

Byllye opened the clinic’s door for Pam in the spring of 1974. It was ready.

PAM

Pam was hired after a month of front office volunteer work. She answered phone calls and helped women fill out paperwork for about a year, then she moved to the counseling department, where she heard patients’ stories and walked them through their options at the clinic for at least half an hour. In the beginning, abortion days were usually Friday and Saturday nights, while “well woman care” (contraceptive and menstrual health counseling) was offered three nights a week. Pam and Byllye said it was one of the first places to focus entirely on women’s health in Gainesville.

“By far, the response was just being so thankful that they were being respected and considered equals,” Pam says. “We were the only clinic in our area for quite a long time.”

Pam quickly became the head of counseling, where she saw many kinds of women arrive at the clinic’s doorstep. Lots of college girls, frustrated that a condom broke or birth control failed them. Women in expensive, wide-lapel blazers with pressed and primped hair, biting the inside of their cheeks with their legs crossed. Black women of all ages from the east side of town for sickle cell tests, which Byllye advocated for, the younger ones in Jimi-Hendrix-style jean jackets combing out their afros. But by far, the clinic’s most common customer was the rural woman, who would sometimes drive hours once she realized Medicaid would cover the cost.

“Oh, no, no,” Pam would say. “Nobody can make you get an abortion. That really is the law.”

She’d explain that there was no right answer. It was important to her that those girls understood they had a real choice.

Most common above all were the women (or the parents of young girls) who — regardless of age or race or religion or wealth — said that they didn’t believe in abortion. That they would never step foot in this clinic again. That women should not be killing their own children. But their situation was special, their daughter was special, and it was an absolute necessity and, please, will you book them an appointment?

“That was one of my harder experiences, actually,” Pam says. “I would look around at the other women there and think, do you really believe your daughter’s more special than these other women? Everybody’s got an individual story. Everybody’s got a reason why.”

Regardless, it was Pam’s job to bond with the women she counseled. She would hold their hands through the procedures and explain everything as it was happening, and then she would lead them into the recovery room. She thought it was so beautiful, watching them lean back into the recliners with a sense of faint relief on their faces.

She stayed at the clinic for a decade, eventually becoming executive director. But soon, the founders, including Byllye, left. It didn’t feel like it used to anymore. Abortion-on-demand was becoming the norm. For the women around them filtering into the open positions, it wasn’t a rebellion, a fight. It was a day job. Quietly, Pam packed up, too, and moved on to other things.

That was before the protests.

AMY AND ERICA AND EMMA AND GEORGE

It was the early ‘90s, and there was a bleeding woman on the operating table. Her limbs spasmed back and forth as Amy Ottinger, fresh from San Francisco, attempted to hold her still while Dr. George Buchanan tried to finish her abortion. Scarlet drops sprayed across the front of Amy’s shirt.

Outside, the anti-abortion movement had begun to mobilize — the bleeding woman had walked in the back door because of the throngs near the front. The Handbook on Abortion, a novel with graphic depictions of aborted fetuses considered the “Bible of the pro-life movement,” had moved into the mainstream across the country. The images were plastered onto homemade signs outside the Gainesville Women’s Health Center, where the counter protesters also rotated between two other abortion clinics that opened in the city: All Women’s Health and Bread and Roses. The protests still persist; I’ve driven past them on these college town roads.

Emma Caplan, all of 5 years old, was the daughter of one of the clinic’s nurses. Her father and his friends, members of Veterans for Peace, would watch the protesters and shield women approaching the clinic for procedures. She would skip rope in front of the protesters to block their path leading up to the clinic, cheekily smiling from ear to ear, curly hair bouncing. Despite their screaming and their signs, she said she was never afraid of them.

Sometimes they were young men, some of them religious leaders. Sometimes college students. Most often, they were older women, hunched over and clutching their rosary beads, praying the patients understood what they were about to do.

Back inside, the woman on the table was having a seizure. She was allergic to the lidocaine — a fact she concealed from Amy and the other employees — that was injected into the cervix during an abortion. But once the procedure began, it couldn’t stop. George had to make sure all of the fetal matter was removed. Amy had to make sure the woman held still. After many minutes of sweat and fear and more blood, they managed to complete the procedure and stabilize the woman. It succeeded by a thread. If the woman had told them about her allergy, none of it would have happened. They would’ve had to turn her away because there was no substitute for the lidocaine. She knew, Amy remembers, the choice she was making.

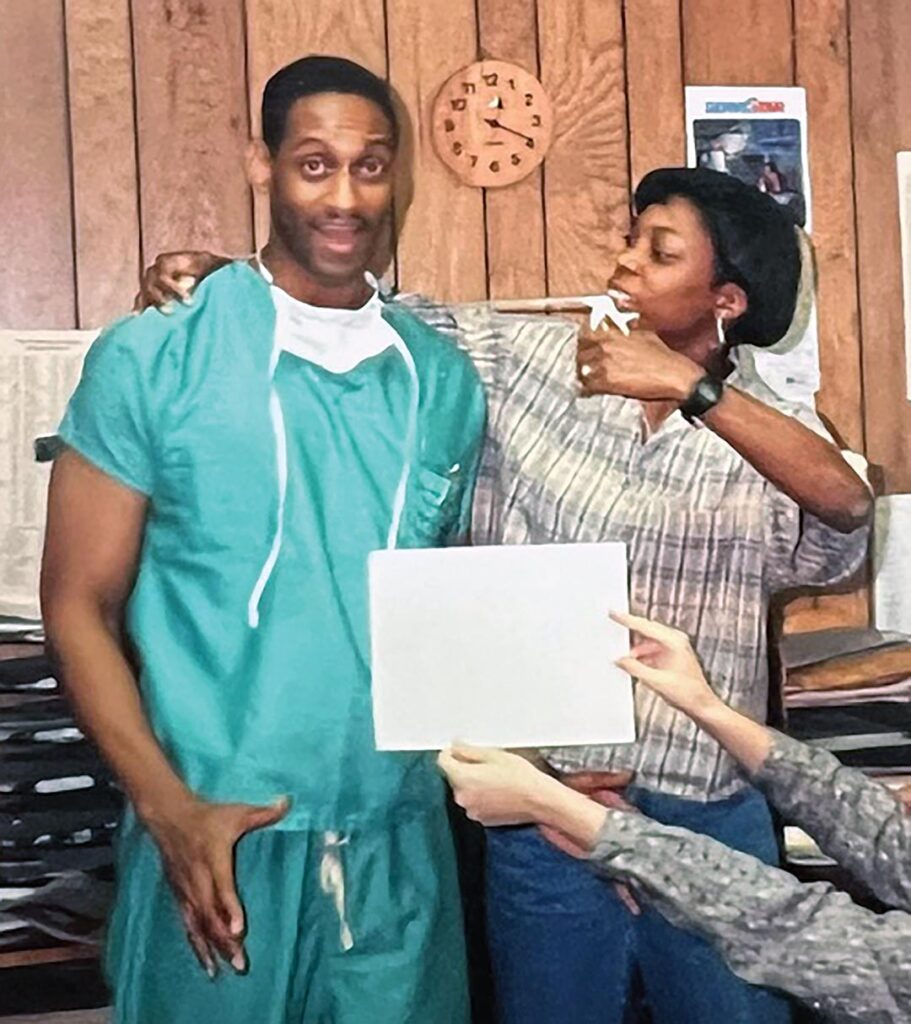

The clinic now performed abortions on Tuesdays up to the second trimester, and on Fridays well into the second trimester, thanks to George’s added expertise. He became the clinic’s medical director in the late 1980s right after finishing OB-GYN residency. As a Black man performing abortions in the South, many of the clinic employees worried for him. He still rode his bicycle straight through the protests on the way to work. Eventually, after a few instances of different abortion doctors getting shot in the 1990s, his coworkers convinced him to let them pick him up at a predetermined location before work. He begrudgingly hid under blankets in the back seat.

As a man raised by his grandmother, George was serious about the women and his work. He attended to all aspects of female healthcare, from checkups to examinations to surgical procedures to help babies arrive healthy. Once, someone asked him how he could fight to save a premature baby at 24 weeks, and then arrive the next night for an abortion at 24 weeks.

“The woman is my patient,” he said, “and I do what she wants.”

His words stuck with the women at the clinic. Many of them repeated it back to me, including Erica Merchant, who was a counselor, like Pam had been decades earlier.

Erica found the clinic for the work and stayed for the community within the wood-paneled walls and shag-carpeted floors. On the nights when George was late (and he often was), the counselors would sit and chat with the women, taking their minds off of the impending procedure by laughing together about the mundane cycles of their lives. She was able to look into the eyes of the patients and see the worry melt away when she set up each step to get them closer to an abortion. George’s mantra — I do what she wants — echoed in her mind as she considered a life in healthcare.

Erica Merchant, who spent most of her college years volunteering and working at the Gainesville Women’s Health Center, sits in her Gainesville home on Oct. 29, 2024. (Alissa Gary/Atrium Magazine)

“What really matters when you’re doing this work with other people? Do you really matter? No,” Erica says. “Other people matter. Who they are, and what they need, and what they think, and their opinions, and their experience. That’s what really matters.”

It’s what made her want to be a nurse. Ironically, that’s why she had to step away from work at the clinic — the full-time counselor job was incompatible with nursing school at UF.

1997

The clinic workers stopped for a number of reasons. They weren’t treating the same number of people because of advances in birth control science and condom effectiveness. And the women who did need services called the new chains of medical facilities, like Planned Parenthood or All Women’s Health, that had effective marketing strategies. This was fine, wonderful even, the women reasoned, but it also meant the small flow of income offered to clinic employees was going to trickle. As is, they were often paid minimum wage. And when a woman expressed concern about paying for a procedure, administration would almost always have the fees quietly waived, and the facility would pay for it out of pocket. They squeezed by for a couple decades, but times were changing.

Erica was a nurse in the psychology field in 1997. She picked up a phone call, pursed her lips, nodded, hung up. She glanced at her husband.

“The clinic is closing,” she said.

“I thought the clinic already closed,” he replied.

It was as if the other person on the phone had told her someone in her family had died. She held her breath for a few moments and then called back.

“Is there going to be a party?”

They had thrown parties for everything: birthdays, anniversaries, announcements, even parties for women they’d grown close to while waiting for abortions. Those celebrations were sewn into Erica’s memory of the clinic.

“Well, I don’t think there’s a party planned,” the person replied.

Oh Jesus, Erica thought, hanging up again. What the f—.

2024

Fifty years after Pam knocked on the door, I sat with Erica outside a Gainesville coffee shop, her round glasses reflecting the evening sun. Her eyes, a sharp gray-blue, cut through the glass, highlighted by her red curls.

Since the phone call, the clinic has been cemented as a thing of the past. Roe v. Wade was overturned. Sleeping bans on abortion, tied up in legal troubles since the 1970s, awakened with a roar, breaking their bonds and unfurling across the country — eight-week bans, 10-week bans, 15-week bans. The ball was back in the state’s courts. Florida still has a six-week abortion ban on the books.

I listened to Erica speak about memories of the clinic. Inside jokes and poignant statements from patients, her recollection crystal clear. She meandered into Ron DeSantis and the Supreme Court justices and third-wave feminism, and then she stopped. She looked at me with those piercing eyes.

“I’m sorry,” she says. “I apologize to you.”

I tilted my head, puzzled.

“Listen, this is our fault. We have to get it back for you,” she continues. “We need to get our asses back in the game. We’re just pissing away everything. Women my age, in our 50s, pissing it away, because we think we have it all.”

I realized that Erica blames herself when she watches the news about the fresh debates on abortion. She stares at the screen and assumes the burden. I never pictured these women like that until now. I had imagined it must feel frustrating, seeing something you believed in so deeply be stripped away, but I had not imagined frustration with yourself.

She told me about her four nieces. How she constantly apologizes to them, too. How the guilt follows her everywhere. It was complacency, she tells me. She and the others got what they wanted, they reaped the fruits of the 1970s laborers and relaxed. They shouldn’t have done that. They should’ve kept fighting.

I didn’t know if I should agree with her or comfort her. My mother is her age, and I’ve never seen her as a complacent woman.

“Mama,” I tell her over the phone one day. “It’s strange hearing this from these women.”

I describe Erica’s apology and her eyes. I tell her about Amy, who was angry that the women in her life let the country get this way, and I tell her about Emma, who watched the abortion debate swing to the other side of the pendulum over the course of her youth and called it complacency.

There is a small pause.

“Yeah,” my mother says, her voice floating in a tone I haven’t heard before. “Yeah. We let it go.”