Lost connection

Challenging a generation’s digital default

January 10, 2024 | story and photos by Matthew Cupelli

This story is from Atrium’s Winter 2024 magazine, which released December 2024.

Seán Killingsworth strolled into an AT&T store ready to change the world.

He wanted a flip phone, confusing a handful of Orlando employees who had to retrieve a SIM card from a sister store. Once they set up his device, they weren’t sure how to connect it to a data plan. They didn’t even know if it was compatible with a data plan.

It was 2018. No one wanted flip phones anymore. Especially not 16-year-olds.

Seán hated the time he wasted on Instagram. Snapchat brought on a hum of anxiety. He’d turn his notifications off. He’d sleep with his phone in another room. He’d delete an app only to reinstall it a few months later. He grew more frustrated with himself for not being able to break the cycle.

“I wasn’t in control of my phone,” he said. “My phone was in control of me.”

The time he spent dawdling on social media prohibited him from actually living his life. To make friends, he thought, he needed to exist completely in the real world.

So he bought a flip phone, trading in one issue for another.

Seán returned to his high school campus, back straight, head up, eager to smile at whomever he made eye contact with. But as the days went by, he rarely met anyone’s gaze.

No one wanted to talk. On the few occasions he struck up conversations, Seán didn’t have a Snapchat or Instagram account to stay in contact.

He realized how difficult it had become to meet new people. Even in high school, an environment specifically meant to encourage connection, most students turned to the dull comfort of smartphones.

Researchers have coined a term for when cell phone use prohibits meaningful interpersonal connection: phubbing. When one person is ready for connection, but another is preoccupied with their phone, it can cause disappointment and a feeling of rejection.

After a year of alienation, Seán was drowning in a sea of missed connections.

Talking with his mom one night, he began crying.

He didn’t find value in existing digitally. But without his smartphone, he didn’t seem to exist in the real world either.

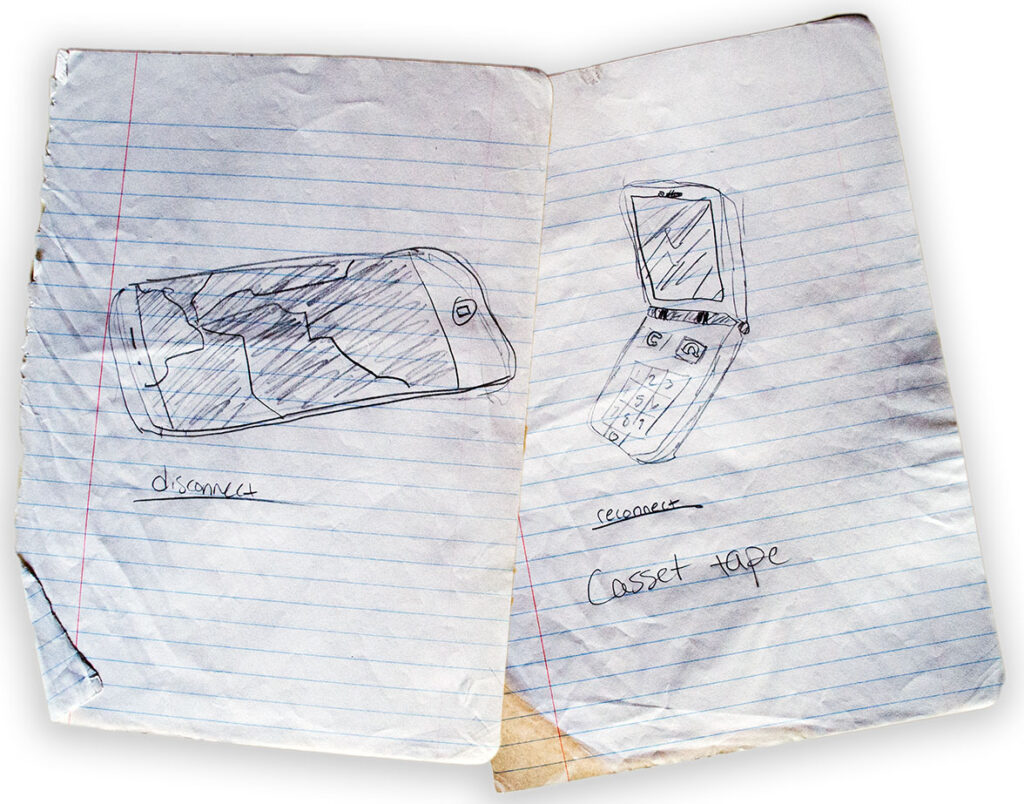

Seán processed his feelings on a sheet of composition notebook paper. Drawing a broken smartphone, he wrote “Disconnect” in stark, bold letters.

He scribbled through tears, wishing his classmates could put their phones down.

Seán drew a flip phone. Under it, he wrote “Reconnect.”

My lone memory of flip phones took place when I was five years old. My dad and I were bored in church. He opened Pong and passed me the phone. I bounced a white pixel between the sides of the screen for five minutes before my mom reprimanded us in a hushed tone. I resumed my attempt to pay attention to Mass.

I’ve been medicating boredom with consumption ever since.

I would sit for hours after school, dumbfounded by the sheer amount of content at my fingertips. With my parent’s iPad propped up in my lap, I would search absurd combinations of terms into YouTube just to see what would come up. Then, I’d watch everything.

Thankfully, I didn’t need encouragement to get outside. My upbringing was still colored by chasing tussock moths and climbing strangler figs. But I am one of the lucky ones.

Millennials, born between 1981 and 1996, are the last generation to recall a smartphone-free childhood. The memories of Gen Z are illuminated by LED screens; in fact, we were almost labeled the iGeneration.

Nearly half of respondents in a 2022 survey indicated they were addicted to their digital devices. In a 2022 poll, 81% of respondents aged 18 to 29 self-reported that they were using their smartphones too much. A 2021 report found that the average teenager spent more than eight hours each day looking at screens.

One of the reasons we are so glued to our screens is because of shifting cultural norms. It’s become taboo to initiate conversations with strangers — why risk rejection or awkwardness when it’s safer to stay on your phone?

Smartphones are designed to be addictive. Our generation’s neurochemistry has been tremendously altered by Silicon Valley elite, some of whom send their children to Montessori schools with limited screen exposure.

While it’s finally caught the attention of American legislators, it’s not a new issue for us. We are a generation thinking in terms of what’s sharable, grappling with a novel anxiety to record and post our lives rather than authentically live them.

We delete, we reinstall. We detox, we relapse. We post, we scroll, we consume.

Feeling helpless is common for Gen Z, and we know smartphones play a key role.

But what can be done when smartphones have cemented themselves as a staple of 21st century life?

It was early fall in 2016, and excitement grew as the van packed with college students left Blacksburg, Virginia.

Without smartphones, the 20 student volunteers couldn’t Google their destination. Crammed into the back of a van, they were left to speculate — and most importantly, talk. That was Laurie Fritsch’s idea.

Laurie, the assistant director of a wellness department at Virginia Tech, urged her students to take advantage of the opportunity to play games and genuinely interact with one another as they drove into New River Gorge National Park and Preserve for three hours of whitewater rafting.

It was a team retreat, she reminded them: “We need to know each other.”

Her job was to ensure students made healthy decisions. Often, that focused on topics like substance use and physical health. But recently, she’d become skeptical of screens.

Even on field trips, she noticed students always seemed to default to their phones. They’d retreat like turtles into the online world at the slightest indication of discomfort. Once phones were out, Laurie said, students rarely reemerged from their shells.

So, for one day, she banned them. She wanted 20 adolescents to experience the simple joy of time outdoors in good company.

Conversations erupted in the white van. Senseless banter and crude jokes filled the vehicle as they amused their way into West Virginia. After rafting, Laurie noticed the same pattern. When nudged, students quickly got over their phone-separation anxiety, and the initial awkwardness was replaced with earnest discussion.

Once Laurie parked the van back at Virginia Tech, one student remarked how nice it was to disconnect for the day, which prompted a chorus of agreement. They chimed in with all sorts of adjectives: freeing, different, relaxing.

Laurie, somewhat confused, reminded them of their agency. She said they could ignore their phones whenever they chose.

They looked at her like she was crazy.

Seán calls it the social wasteland — when you look up from your phone, ready to branch out and meet someone new, and your opportunities for connection have already been thwarted. The social wasteland is what you see when you look out onto a crowd of strangers, and no one looks back.

In his senior year of high school, he formed a club where, he said, “the people you’re trying to interact with are actually capable of paying attention to you.” Anyone could join. The only stipulation was members were required to lock their smartphones away in custom magnetic bags.

He named it the Reconnect Movement.

The first collegiate chapter of Reconnect began at Rollins College in Winter Park. The club got 90 sign-ups within two weeks of its announcement, Seán said. Soon, he opened a chapter at the University of Central Florida, followed by the University of Florida.

Then Laurie reached out.

After her trip to West Virginia, her feeling that smartphones were harming young adults solidified. She saw that students were unhappy but helpless, searching for an excuse to put their devices down. So, she developed a curriculum to target digital wellness, aiming to give students that reason.

Boxes in dining halls dared students to stash their phones during mealtimes. Thoughtful conversation-starting cards circulated in public spaces throughout campus. Mindfulness challenges enticed students with goodies.

But she knew not every school had the resources to plan, fund and execute elaborate anti-smartphone initiatives. Student organizations like the Reconnect Movement, she thought, could help fill the void.

Laurie invited Seán to speak at a conference on college students’ digital well-being.

He now advocates for safe social media policies in Washington, D.C., juggles speaking gigs at Harvard and James Madison Universities and meets with Reconnect chapters at colleges across Florida. Seán attended college in Orlando but dropped out to focus on the Reconnect Movement. He works full-time for his family’s cleaning company to keep his apartment lights on.

Per club rules, Seán locked away his black iPhone 14 in a gray sleeve called a Yondr Pouch.

It had been nearly three years since Seán graduated high school, and today was a big day for the University of Florida’s Reconnect chapter. It had survived its first semester, and members were about to elect new leadership.

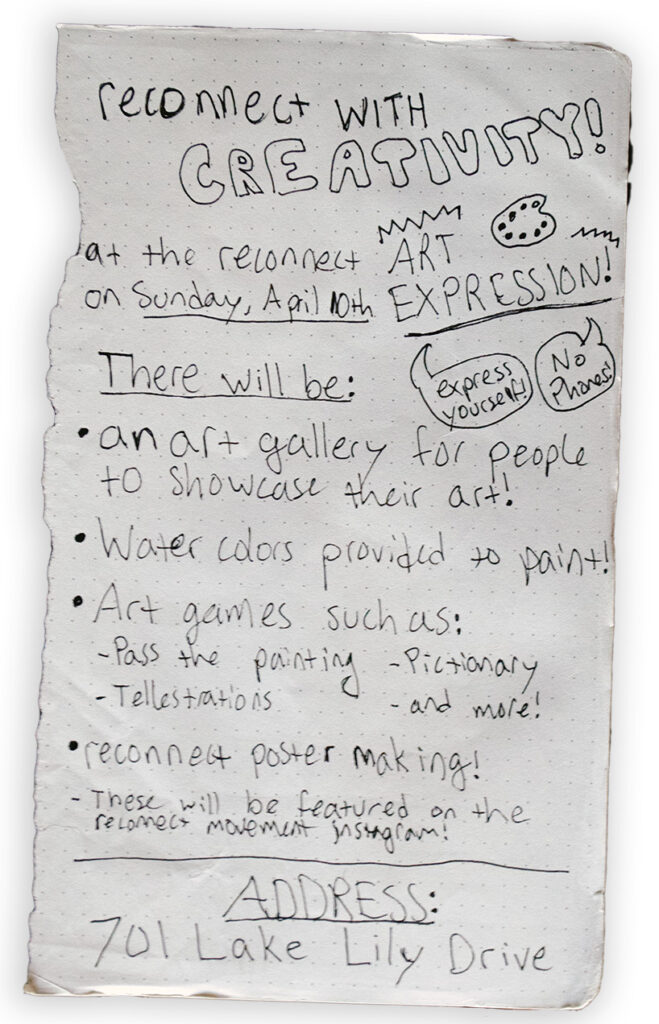

A flyer Seán made in his senior year of high school to promote one of the first Reconnect Movement events. Expressing creativity through arts and crafts remains a hallmark of Reconnect meetings. (Matthew Cupelli/Atrium Magazine)

The pouch by his side, Seán joined the student members sitting atop a mosaic of Bohemian rugs in a campus park. Their idle chatter about buying turntables and trading records filled the afternoon air, paying no attention to the devices they’d trained themselves to ignore.

The former president, Eva Wolpert, stood and thanked everyone for a successful semester. Before she conducted elections, she spoke about the importance of preserving phone-free spaces — a tone that many echoed in their speeches.

With new officers selected, a guest led a group yoga session to release any lingering anxiety. Seán moved through the poses but couldn’t quiet his thoughts. Instead, he thought about how to organize the new leadership and his growing community. This was still a new reality for the 22-year-old digital wellness leader.

Once, he had no social group. While he blamed his seclusion on smartphones, Seán knows that they’re here to stay.

He used to wonder what one person could do to resist such a hollow existence. Now, with his iPhone tucked away, he felt encouraged by how many others wanted to do the same.

Matthew Cupelli

Matthew Cupelli is the multimedia editor of Atrium Magazine. In his free time, he likes getting lost in the woods, discovering new music and causing healthy amounts of mischief.