Siblings born together are said to have a supernatural bond. My brother and I do not.

December 9, 2022 | Essay by Marlena Carrillo | Illustration by Bryce Brown

This article is part of Atrium’s Winter 2022 issue. To view the print edition online, visit our Issuu here.

In my junior year of college, my roommate persuaded me to watch “The Haunting of Hill House.” I don’t watch scary TV shows for my peace of mind, but I grew attached to the Crain family.

The two youngest siblings, Luke and Nell, are twins. In the fourth episode, their dad gives Luke a hat. When he asks if Luke likes it, Nell answers for her brother, saying he loves it.

“How do you know that?” their dad asks.

“It’s a twin thing,” she explains.

My roommate turned to me. “How about you?” she asked. “Do you guys have a twin thing?”

She was referring to my brother, Tyler – or Ty – who is three minutes my junior. I’d been asked that question before; it was an interest prompted by movies like “The Parent Trap” or anything with the Olsen twins. How could you be a twin and not have the twin thing?

So, I answered without hesitation. “Yeah. Kind of.”

The question is more complicated for me.

Tyler has cerebral palsy. He can’t walk or talk.

Since birth, I’ve been the lone mouthpiece of our dynamic duo, give or take a few well-articulated murmurs.

If Ty had something to say, it was up to me to say it.

But could I? My brother is easy to please if he gets to be around people, watch movies and enjoy a good meal. But could I sense it? If he’s sad, would I know? If he’s missing something important — something so paramount to his happiness, but he can’t say a word — would I be the one to hear it?

I didn’t tell my roommate that night, but I knew my real answer: I didn’t feel it at all.

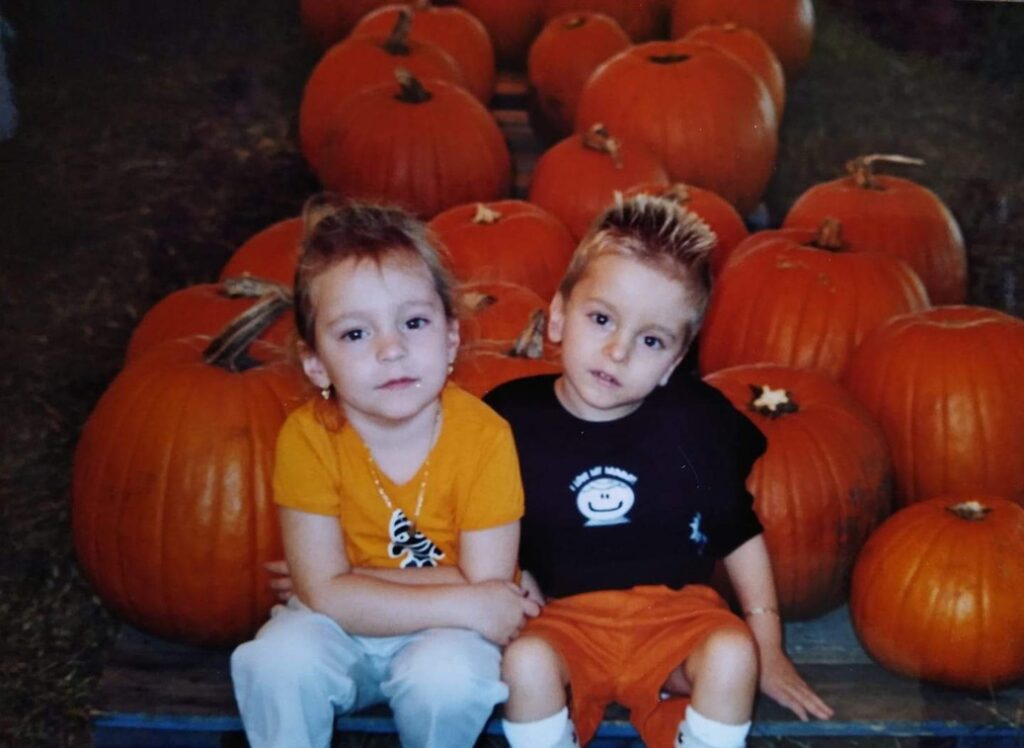

Carillo and her twin brother, Tyler, visit a pumpkin patch at 4 years old. Tyler was diagnosed with cerebral palsy at 6 months old, for which he has required constant care his whole life. (Photo courtesy of Marlena Carrillo)

It’s a sickening thought, even to write. How could you have a twin sibling, a phenomenon more fascinating than two Lindsay Lohans, and have no telepathy, secret gestures or catchphrases? Especially when your other half is wheelchair-bound, mute and, according to his individual education plan, helpless.

As fraternal twins, Ty and I weren’t as dazzling a spectacle as identical ones. While my grandmother prayed to the Lady de la Leche for our birth and proudly predicted we would be boys, I ruined the odds. My mother wouldn’t let it slide, either. She had my ears pierced after our first birthday to enlighten the strangers congratulating her on her sons. It didn’t work.

The twin experience fascinated me, but I didn’t share it. In elementary school, identical twin boys would walk into class with the same haircuts and outfits, all the way down to their Crocs.

That didn’t feel like Ty and me. My brother and I grew up in separate lanes, a consequence of our genders and Ty’s condition. While I was playing with Barbie dolls and taking honors classes, he was watching Elmo and doing physical, speech and aquatic therapies weekly.

Perhaps other twins grow up linked to one another like two soup cans connected with yarn. My relationship with Ty felt more like a call with someone who left the phone dangling on their end of the line.

I was at once an older sister, a nurse, a babysitter and, though I’d never say it out loud, a mother.

When Ty puked in Target, I was the one who got the bag. When he hollered gleefully at night, I was the person unable to sleep. And when 5-year-olds stared slack-jawed at us in the mall food court, it felt like they were staring at me.

I was angry and sad for my brother. No one should be looked at like a derogatory alien from Mars. But more than that, I pitied myself for being subjected to it at all.

That’s not to say Ty doesn’t live in my head the way the Crain twins describe; he lingers in my mind even when I’ve left home. He’s there when I say, “I have a brother,” tiptoeing around the innocent questions like “What classes does he take?” and “Have I met him before?” He’s in my dreams of the future, right next to my husband and kids — because where else would he go? Even when he’s two hours away, I think I hear him making his usual mm and ss sounds from my dorm. Is he saying Marlena? Sister? Mom? It ends up being the athletes down the hall.

Ty and I have an emotional connection, even if it isn’t the paranormal twin thing. As his sister, I loved him, hated him and hugged him as often as I pulled his hair.

Still, a piece is missing. The Twin Thing makes your sibling out to be a soulmate — your partner in crime from the moment you’re born. When you have a twin, the TV shows fabricate a world where you’ll never be alone again, but I grew up doing everything on my own.

I feel guilty yearning for something that was never there. If there are twins who sense each other’s emotions by thinking, how could I feel nothing? In a world that sees Ty as just an extra place setting and a wheelchair to hold the door for, shouldn’t we share some supernatural connection that sets us apart?

The truth is, like most siblings hate each other sometimes, I hated Ty. I cared for him like a parent. When everyone else was asleep, I would tiptoe into his bedroom, turn his TV off, tuck blankets beneath his freezing toes and whisper how much I love him. But as a sister, I blamed him when things went wrong in my life.

When Ty had his first seizure, I felt debilitating fear for the first time. I was the only one in the room at first, holding on for dear life as I dialed 911 and scrambled for a toothbrush to keep him from choking on his tongue. My parents took over when they arrived. I stood back paralyzed, too frozen to cry.

When I was in middle school, and Ty would spend hours at a time screaming and crying in unknown pain, I screamed on the inside. When my mom drove my brother to the emergency room for the second time that month, I had a panic attack in the back of my high school newsroom.

Ty and I weren’t two passing ships, but two swimmers stranded in the middle of the ocean at the same time. No one questioned who needed to be rescued first. Sometimes, though, I wished there was room in the lifeboat for me, too.

As an adult, I know my brother isn’t at fault. The circumstances hurt us both — him more than me. Neither of us got to choose our roles. I could’ve been anyone’s sibling, but however the stars aligned, I was his. For whatever cosmic reason, he needed me. I think part of me needed him, too. Maybe that was our magical connection all along.

My friend’s mom is a twin. She recounted a story of when she lived in Washington, D.C., while her sister was living on Long Island. One night, she went to the hospital with severe stomach pains, and they kept her overnight because the doctors couldn’t determine a cause. She returned home the next day to countless messages on her answering machine. Her twin had given birth the night before.

I asked if the bond she shared with her sister would be the same without the mystical twin phenomenon. She admitted she doesn’t think they would be as close if they were regular siblings.

But a King’s College London survey found only one in five identical twins say they’ve experienced some form of telepathy. For fraternal twins, it was one in 10.

Maybe the twin thing is like most Hollywood tropes: fictional. After all, Lindsay Lohan’s twin was CGI, and Tia and Tamera weren’t really twitches. I say the twin thing depends not on extrasensory perception, but on the nature of the sibling bond itself.

From my living room in Gainesville, I can’t tell how Tyler is doing in Tampa. I try not to let it bother me. Perhaps one day, the guilt will leave me. I’ll feel relief in its place.

Maybe Ty will feel it, too.

Marlena Carrillo

Marlena Carrillo is an assistant editor with Atrium. She previously interned for Irving Publications, where she wrote for Giggle and Wellness360 magazines. She has also reported for WUFT and the Independent Florida Alligator. When Marlena is not writing, she is guzzling chai lattes, caring for her plants and being an avid Black Widow fan.