800 miles, no shoes:

One migrant’s journey to freedom

Through rain, thorns and armed men, Rogelio trudged barefoot for hundreds of miles. His only guide? The desperate hope for something better.

Jacksonville, Fla., Tuesday, Feb. 18th, 2025. (Anna Edlund/Atrium Magazine)

October 10, 2025 | story by Nathan Thomas

photos by Anna Edlund

This story is from Atrium’s Spring 2025 magazine, which released April 2025.

Click here for the translated story.

After two days wading through knee-high mud, Rogelio Fernandez watched his Timberland boots disintegrate. With waterlogged pants and bare feet punctured by thorns, he pushed forward, knowing he couldn’t turn back.

He had just embarked on the most dangerous leg of his journey to the United States, across the roadless land bridge connecting North and South America, a 60-mile trek through thick tropical rainforest and landslide-prone terrain.

He was crossing the Darién Gap.

Robbers, drug smugglers, panthers, snakes and the jungle itself form a crucible for migrants seeking a better life in the U.S. Over 170 people died trying to cross the gap in 2024.

Now, as Rogelio rebuilds his life in Jacksonville, Florida, as a business owner working in air conditioning and heating repair, he still carries his story of arrival — one of strength, will and the unyielding desire to live free.

Leaving Cuba

Rogelio first tried to escape Cuba in 2012, applying for tourist visas to Uruguay, Mexico and the Dominican Republic. He was rejected each time, until 2017, when he secured a visa to visit French Guiana, a region in South America.

After saving money sent from relatives in the U.S. and selling all of his property, he compiled a bag with the items he imagined he would need to make the voyage: clothes, non-perishable food, a thousand American dollars, his sturdy Timberland hiking boots and a carne asada, a taste of home.

He managed to convince his cousin Elaine to join him. They boarded a plane to Guiana with no plan.

In a town with bright orange and yellow high-rises and street vendors, Rogelio ran into a friend from Cuba who was buying clothes to sell back home.

“He told me that at the motel where he was staying, there was someone dedicated to organizing crossings into Venezuela,” Rogelio said.

Smugglers, scams and South America

After securing his passage, Rogelio was taken to a makeshift camp by the Cuyuni River, which forms the natural border between Venezuela and Guyana.

“We left at night and were on the water for 24, almost 25 hours,” he said.

They traveled in a long, shallow boat — what Cubans call a “cigarette boat” — close to the water with four motors in the back.

“We were practically flying, bouncing off the water,” Rogelio said.

The journey was one of constant unease — fear hung thick in the air as Rogelio and over 20 other migrants crammed together, shoulder to shoulder, each praying they’d make it across undetected.

The smugglers, meanwhile, spoke a jumble of French and English that Rogelio couldn’t understand. He strained to catch any shift in their tone, trying to read the situation by instinct.

“From listening so much — the preoccupation, the stress — when we finally got to Venezuela, and people started speaking Spanish to me, I didn’t understand them for an hour,” Rogelio recalled.

Once they arrived in Venezuela, Rogelio’s smugglers took him to a rundown motel where they exchanged his American dollars for Venezuelan bolívars. They warned him it would be impossible to buy anything with dollars in the country.

“Pretty soon, I realized it was a scam,” Rogelio said. “The bolívars are worth less than nothing.”

Still, he couldn’t help but laugh when he saw locals paying for their meals with stacks of bills feet high.

Soon enough, the smugglers informed him of the next step: They would sneak his group into Colombia.

“If they stopped us on the way, we were supposed to say that we were doctors, on a mission in Venezuela,” Rogelio said. He couldn’t help but picture himself — weary and unshaven — standing there, trying to pass for a doctor.

His drivers, noting his appearance, insisted that he lose his beard. “You’ll look more credible,” they said, sure that a clean shave was the key to convincing the border guards.

Finally, he arrived at a small village, the last stop before the jungle he would have to cross on foot. They took a small canoe to a sandy bank in the jungle, where a cove, a dock and a ranchón — a wooden structure with a roof made of leaves and branches — awaited them.

To Rogelio, the scene looked like a movie in Hawaii. It was beautiful, he thought.

But the peace didn’t last.

Two teenagers appeared out of the shadows, one with a pistol at his belt and the other with a rifle slung over his shoulder. They introduced themselves as the guides who would take them through the Darién Gap, their demeanor disturbingly calm.

They said they were going to pick up another group to join them. Rogelio and Elaine were to wait at the hut until the guides returned.

Each passing hour charged Rogelio and Elaine with nerves, like toys wound too far. One day dragged by. Then two.

When the pair heard that another Cuban, a bald, easy-going man named Santiago, was also anxious to leave, they decided: The three of them would make the trek on their own.

Hell in the jungle

The jungle was relentless, thick with insects, snakes and the constant threat of predation. The trees seemed to close in on them as branches scraped at their skin, but the worst part was the ground.

The rain came without pause, turning the floor of the jungle into a soupy mess — a knee-deep mire of dirt, water and rotting vegetation. Creatures that thrived in the sludge scurried beneath the surface, while sharp spines lay hidden, waiting to sink into bare skin.

After two straight days of walking, Rogelio’s trusty Timberlands — brought all the way from Cuba — finally gave up, splitting at the seams. When Rogelio peeled them off, a layer of skin came with them.

For the next 800 miles, until he crossed into Nicaragua, he traveled barefoot.

He stepped on a spine every 30 to 40 minutes.

The trio’s food supply consisted of cans of tuna and sugar. Rogelio and Elaine stopped to eat once a day, downing the extra oil from the tuna cans for some extra fat and energy, trying to push the hunger out of their minds.

It didn’t help that Rogelio’s clothes were becoming a burden.

He cut his pants, made of a heavy material, into shorts, hoping to relieve some weight. At night, he used the pant legs as a blanket, wrapping himself in the fabric to shield against the constant dripping water. Sleep came in fragments, interrupted by the howling rain and the constant, gnawing ache in his muscles.

On the third day, they ran into a group of Colombian drug smugglers. Each was armed with a long rifle.

Rogelio had heard stories of how men like these assaulted people. Instead, these men told him his group was lost and pointed them in the right direction.

“Look for a hill, turn, and try to cross once you get there,” the men said.

Grateful and relieved, Rogelio’s group trekked onwards. The terrain began to shift as they hiked upward, convinced they had found the landmark. They pushed on for another seven hours.

On the descent, Rogelio, exhausted and in tremendous pain, thought he had stepped into another dimension when his senses picked up something completely foreign to the jungle.

Spaghetti.

The group slid down the hill, feet slipping on muddy ground, until they reached a group of Haitian men cooking spaghetti over a gas burner in the middle of the Darién Gap.

After three days of nothing but canned tuna fish and raw sugar for dessert, the promise of a hot meal made them delirious.

“It was the best restaurant I’ve ever been to in my life,” Rogelio said.

After the meal, they called it a day and went to bed. But it wasn’t long before they awoke to the sound of rushing water.

The river, previously calm, was growing by the second. Rogelio watched the water rush toward them, three meters, then two meters, then one meter away, until the group ran back up the hill they had come down.

They spent the night walking and crossed the river at daybreak. For the next two days, they slogged through marshy flatland, their bodies heavy with fatigue, their feet a bloody mess. On the seventh day, they ran into the Panamanian military.

The officer in charge told them to head to a camp in Lajas Blancas, where they would be vaccinated for any diseases they might have picked up in the jungle.

Elaine saw the body first.

It was an older man, mid-40s, who had fallen over on the road. His skin was already yellow.

“It looked like he had been dead for about three days,” Rogelio said. “And by the clothes he was wearing, we could tell he was Cuban.”

This man had walked the same brutal path Rogelio’s group had, carrying the same hopes, the same desperation. Did he get to speak to his family before he died? Had he dared to dream of reaching the U.S.?

For a long moment, they stood silent.

Through Costa Rica

In the camp, after their vaccinations, the military gave them an order: They had 72 hours to leave Panama.

“Supposedly, they tell you that so that you go back where you came from,” Rogelio said, “but we picked up and headed north.”

At the border, a police checkpoint stood between them and the next leg of their journey. Officers were checking papers to ensure no one slipped through.

Rogelio and seven others waiting near the border formed a plan. They would move quietly, stick to the roadside brush and hope to avoid detection.

The migrants crouched low, inching forward in silence, when the roar of an engine shattered the night. A jeep full of police officers came barreling down the path, rifles at the ready.

Everyone scattered. Rogelio and Elaine threw themselves into a bush and lingered there, listening to the police call out “Here’s one!” and “Here’s another!”

Finally, an officer shouted, “There’s two left, keep looking!”

Rogelio’s breath caught in his throat. Every muscle tensed.

“I don’t want to keep going,” he told Elaine.

She turned to him, unwavering.

“Muchacho, we’ve come this far, we’re not going back.”

The pair stayed hidden for three hours, waiting for the search to fade. When the jungle felt safe again, they rose and pressed on, walking parallel to the road until they stumbled upon a small house.

Three older women lived there, one in her 40s and the other two in their 50s or 60s. Rogelio recounted his story, and the women warned him not to keep going. The police were waiting ahead.

They decided to wait a while, anxious and grateful for the women’s hospitality.

Their hosts gave them food and medicine, in part to treat Rogelio’s pounding headache. One of the older women walked them to a bus stop, shielding them with an umbrella as rain drizzled down. When the bus arrived, she turned to them with quiet conviction.

“Have faith. God will help you.”

Rogelio and Elaine got off the bus at the Nicaraguan border. Here, they ran into a group of Cubans who had been stuck at the border for three months.

Two couples in the group had been working, saving what little they could to pay guides to take them across. But each time they made enough money to try, they were robbed in the jungle.

“The same people that said they would take them are the people that laid the trap to assault them,” Rogelio thought. He knew he couldn’t risk it.

So he made a quiet decision.

“We’ll say we’re going for a walk, and we’ll leave. With God’s favor, we’ll get there.”

Mercy and malice

After trekking through the night, Rogelio and Elaine came across a house nestled in the mountains. The elderly man who lived there informed them they were already in Nicaragua and extended the same warning as the women from the previous house: Don’t go any farther. There are police down the road.

Deserters who flee Cuba and are caught in Nicaragua face being sent back to their country of origin. Furthermore, anyone caught helping them risked prison.

“The people in Nicaragua are very afraid of helping Cubans because they could go to jail,” Rogelio said.

Still, the old man let them stay. For two days, he hid them in his house, providing food and water, expecting nothing in return. Then he reached out to someone who could help.

Two young bricklayers arrived, offering to exchange Rogelio and Elaine’s dollars for Nicaraguan currency so they could buy cell phone chips and supplies.

Rogelio spent the extra money on new shoes, a pair he remembers vividly — blue and green with white stripes.

With a working phone, he called his family in the U.S.

He was alive. He had made it to Nicaragua.

His family sent him some cash for the rest of the journey. It was enough for him and Elaine to purchase a pair of red bicycles.

At the next police checkpoint, they simply pedaled through, blending in with the locals.

Once safely past, they found a bus to take them to the Nicaraguan border Honduras, where they were granted passage on the same bus to Guatemala. There, Rogelio reunited with an old friend, one who knew a taxi driver who could drive them the length of the country.

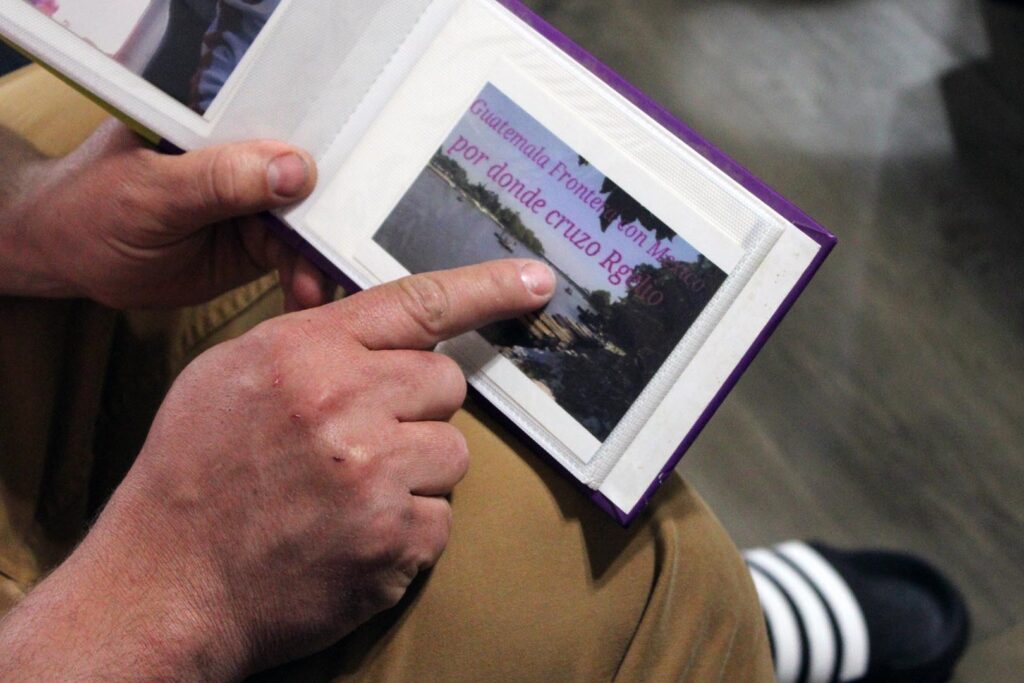

By taxi, he and Elaine reached the Suchiate River, the border between Guatemala and Mexico. To cross, they climbed onto makeshift barges, nothing more than tires lashed together with wood.

Just 50 meters away, the Mexican police watched from a bridge. They didn’t move as Rogelio and Elaine floated across.

The pair walked to a nearby town called Tapachula, where an entire underground economy thrives on the needs of migrants.

People whispered about fixers who could secretly acquire anything — SIM cards, safe houses, even cars for the right price. It was here that Rogelio and Elaine found someone willing to drive them north, to the edge of cartel territory.

For hours, they drove. Hours stretched into days. They passed the time talking, until the course of their journey changed with a single word.

“I let it slip,” Rogelio said. “Just one word in casual conversation: ‘Cubano.’”

The driver stiffened. His eyes flicked to the rearview mirror. The silence grew heavy. Suffocating.

Something was wrong.

The driver of the car finally spoke. “Cubans are like racehorses here.”

To kidnappers in Mexico, Cubans are attractive targets. They believe most Cubans making the trip north already have family in the U.S. supporting them. The opportunity to extort wealthier American families is often too good to pass up.

Sure enough, the driver delivered them not to safety but to a house where they were held hostage.

They were held for three days, the kidnappers demanding $2,500 apiece from their families. If they didn’t pay, they threatened to send a finger, then a hand.

On the third day, Elaine broke.

“Where am I? Who are you? What am I doing here?” she asked Rogelio. He had never been more terrified.

“At that point, I was thinking that the best thing that could happen at that moment was that the police would come and deport us to Cuba,” Rogelio said. “I’d rather live in Cuba than die in Mexico.”

Their families, meanwhile, scrambled. They sold jewelry and took out predatory payday loans, scraping together whatever they had.

They couldn’t reach $5,000. But they got to $2,400.

It was enough. The kidnappers took the money and dumped Rogelio and Elaine at the edge of cartel territory.

The border

The two boarded the last bus of their journey with a plan. The bus would take them close to the U.S border, but they wouldn’t risk staying on too long. A few miles before the crossing, they would get off and walk the rest of the way, avoiding any immigration checkpoints that could send them back.

The hours stretched on, the landscape rolling by in a blur of desert and dust. They kept their heads down, avoiding attention, even when someone came by to offer them snacks.

When they thought the time was right, Rogelio and Elaine rose from their seats and made their way to the front of the bus, adrenaline pumping once again. Rogelio leaned towards the driver and made his request:

“We need to get off here.”

He pleaded their case to the driver, who looked at them blankly before cracking a smile.

“We crossed into the United States a few miles ago,” the driver said.

Rogelio’s breath caught in his chest.

“I couldn’t believe it. It was so much work to get there and we got in almost by mistake,” he said.

At the bus station, he and Elaine found a border patrol officer and surrendered. They pleaded for asylum. The United States granted it.

From there, it was just one more journey — but this time, in the safety of the U.S.

Rogelio’s family was waiting for him when he arrived in Miami. After nearly two months of constant peril, of running, hiding and barely holding on, he could finally breathe.